When I applied to the residency, it was on the basis of a video project I had been working on for a number of years. In 2020, I finished a two minute video poem on the archive as photographed by her security cameras. It summarised my amazement that documents and books were preserved and available to the public. When I sent my proposal to Andreas Züst, I planned to expand the video beyond the pixilated archive of the security camera by listening to the wood on wood scrap of page turning and watching the books interconnected on their shelves like sinews of a sleeping giant. My goal was to return to the physical. When I came to the Alpenhof, I did accomplish my goal, but not in the way I had planned.

In Edgar Allen Poe’s story “The Gold-Bug,” the main character is a bookish man whose life is changed not by a book but by a bug he encounters on a hike. He comes to believe that this bug will lead him to buried treasure and claims that it is “the index to his fortunes.” Like many bibliophiles, he cannot encounter the outside world without the two dimensional world of the library overlaid on top. An index is an alphabetical listing of all the topics of note inside a book, with page numbers wherein they are mentioned; but as most bibliophiles and frustrated student researchers find, many books have indexes that do not list all topics of note. Obscure poets are ignored; the Cleveland Zoo; the three mentions of the Throwing Muses that proved that your favorite contemporary poet shared your teenage love of this post grunge band. But most important for our uses here: the index points away from itself. The bug would not make the bookish man’s fortune because it was a rare entomological find; nor the bug looking and weighing as though it were made of gold, so he could fool a jeweller into paying for it. No, if only he could decipher the secret language, this bug would lead him to page 251, Captain Kydd’s hidden treasure. He almost doesn’t succeed, his obsession with deciphering the hidden language having led his best friend to wonder whether he should lock him up until his delusion has faded. Yet for our bookish hero, his success relied upon his freedom of movement. As does mine.

Once arriving in Oberegg, I walked the area frequently. I walked 8 kilometers to Oberer Gäbris, and during much of the walk I kept looking at my soles, convinced by the stench that I had walked on cow manure and that was how the smell was following kilometer after kilometer, over mountain pass and woodland. No, there was nothing on my shoes. The land stank. I loved it.

It was April, it was calving season, and as an Irish visitor who had grown up around cows said, “These don’t look like cows! They’re supermodels.” My artistic query was: how to make an object that honors this particular archive in the heart of the Appenzell? I gathered linden tree limbs that were left in the crook of a tree, and may have once been used as walking sticks by the many hikers in the region. I photographed the eyes of calves and transferred them onto archival gloves. They recalled the Eye of Horus, which protect from evil forces, and relate to the moon; Horus himself does not relate to cows, but the Greeks worshipped Io, a bovine goddess connected to the moon, who was guarded by a shepherd with eyes in each of his hundred hands, who was called “All-seeing.” In Vedic astrology, feeding cows is prescribed for those with problem planets in their birth chart; those with a troublesome moon, for example, are told to feed cows on Mondays.

My goal coming to the Bibliothek was to explore the physical. I thought it would be through documenting books, but instead it was by creating a site specific apotropaic talisman.

Text: Sammar Al Summary

April 2022

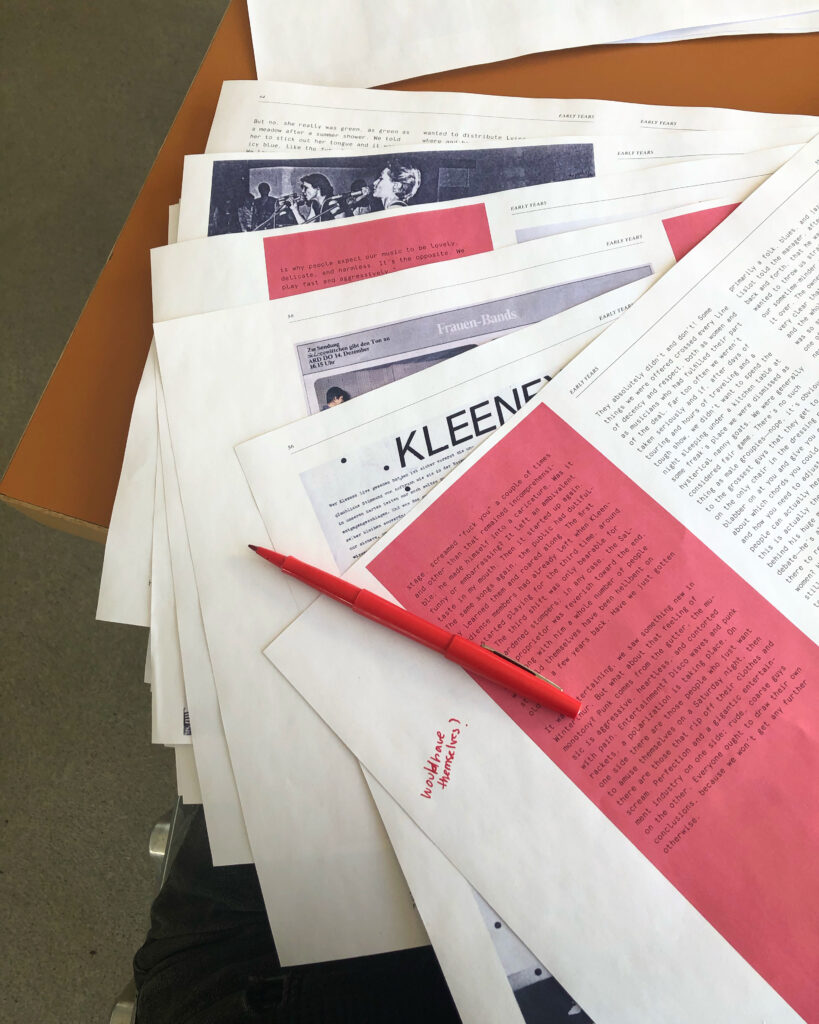

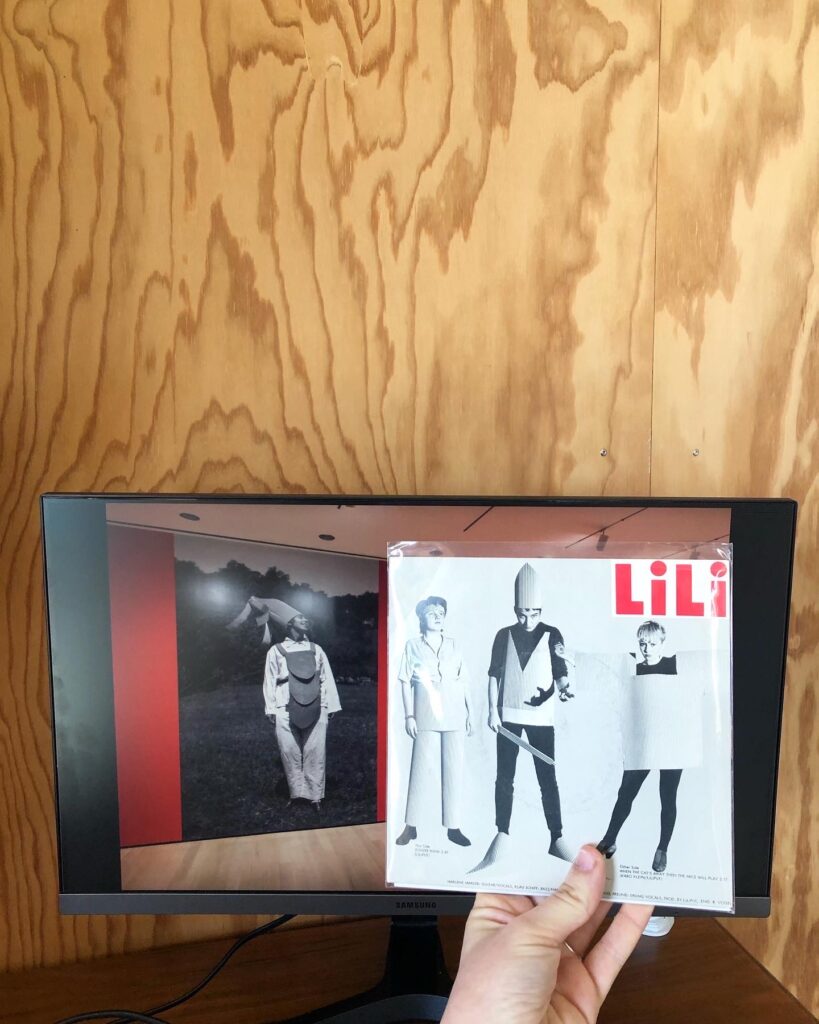

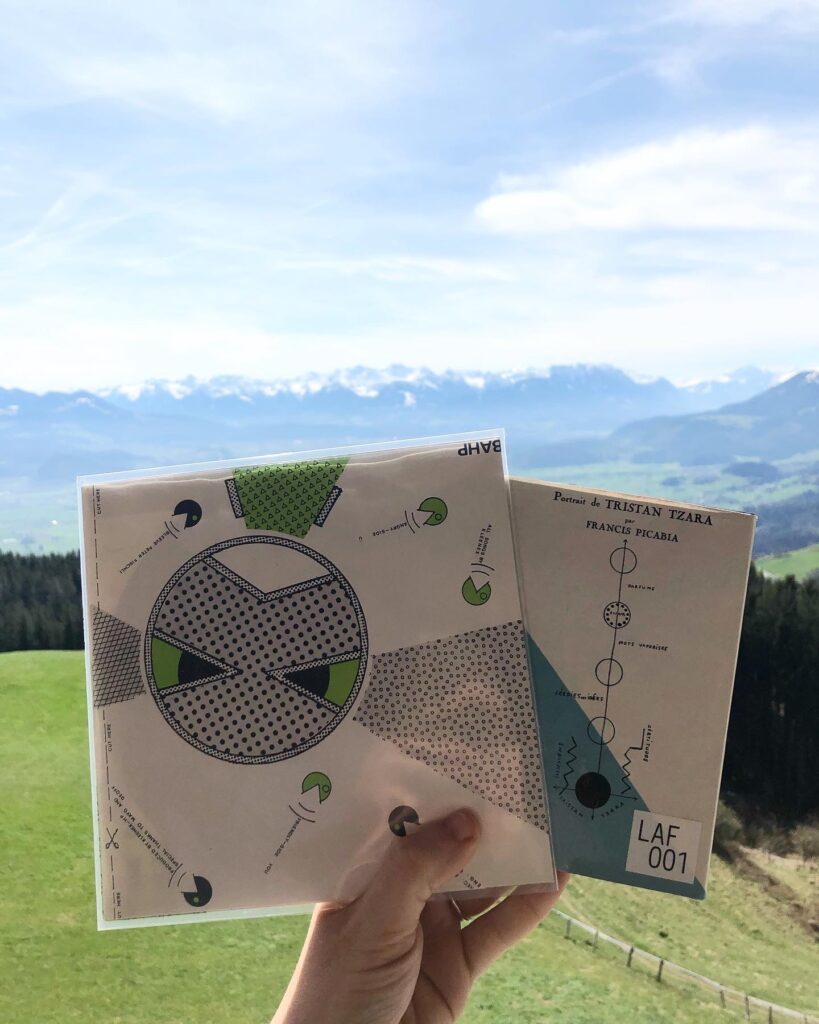

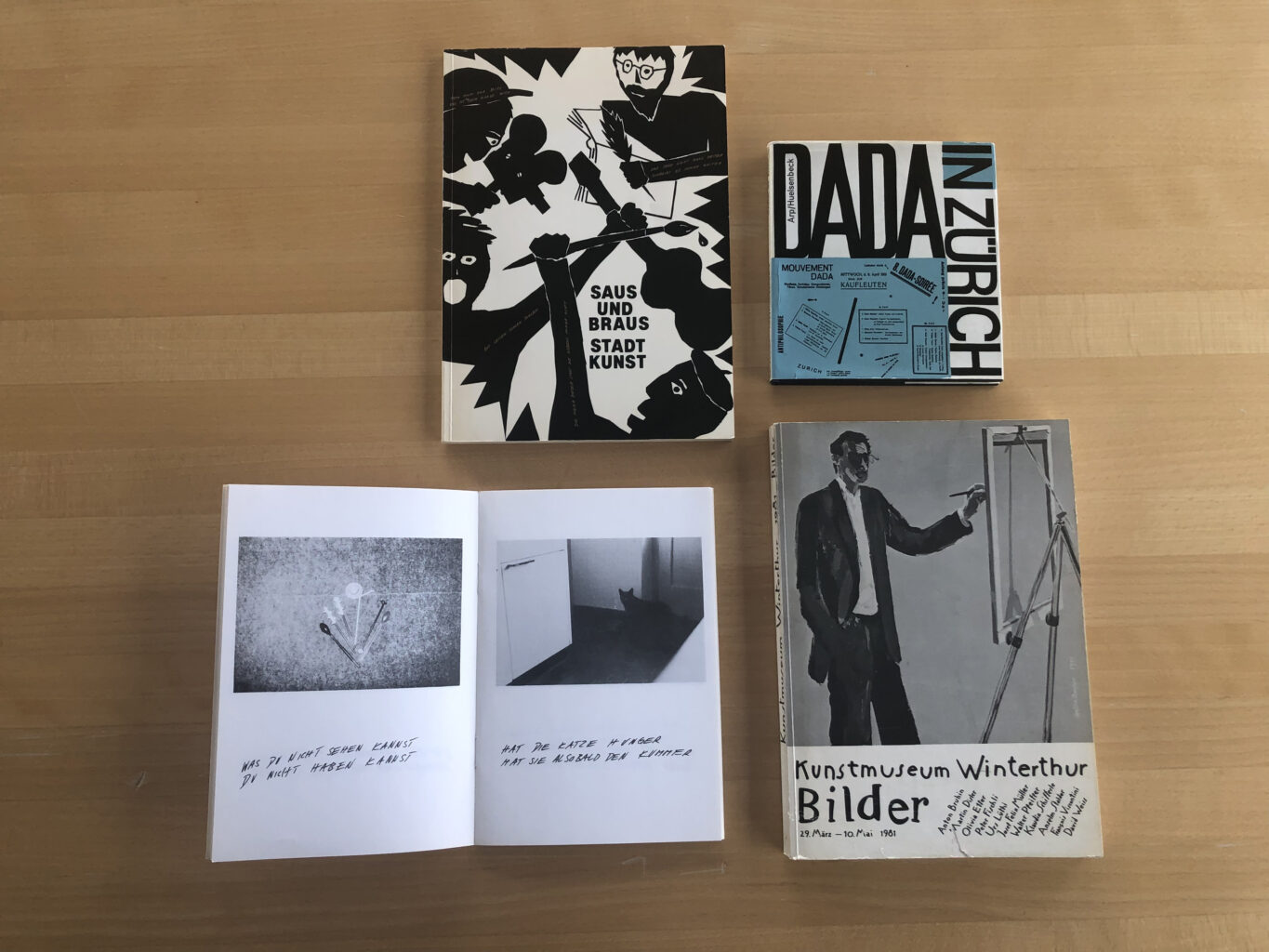

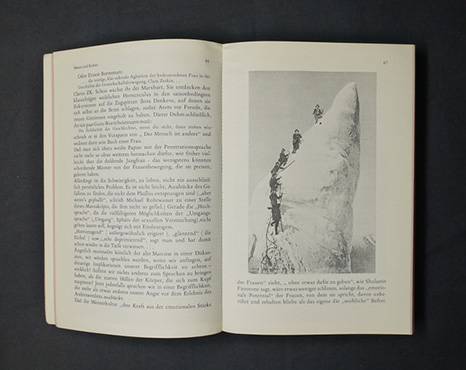

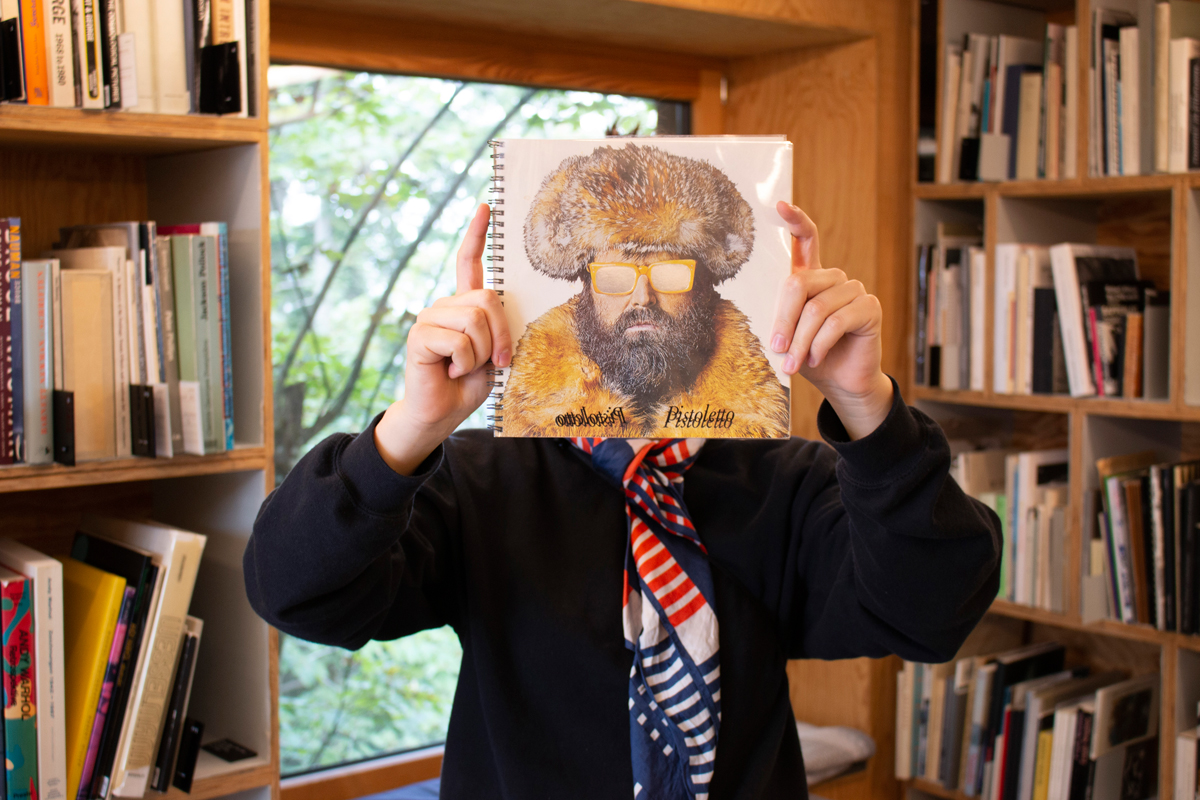

I came to the Alpenhof to make a book. For five years, I have been working on an English-language translation of Marlene Marder’s diary, originally published in 1986. Marder was the guitarist of the Swiss bands Kleenex and LiLiPUT (the second a natural progression of the first!) and her diary is a strange and fascinating text, her personal accounts of the mundane and sublime elements of playing in a rock’n’roll group set alongside reproductions of press clippings, reviews, interviews, photos, flyers and more.

Marder and Kleenex/LiLiPUT existed at the center of a particular punk-cum-art milieu in 1970s/80s Zurich. Impossibly cool-looking (and with great tunes to boot!), they are more beloved outside of Switzerland than within, though knowledge about the band and their story is limited, thanks to the available information being mostly in German.

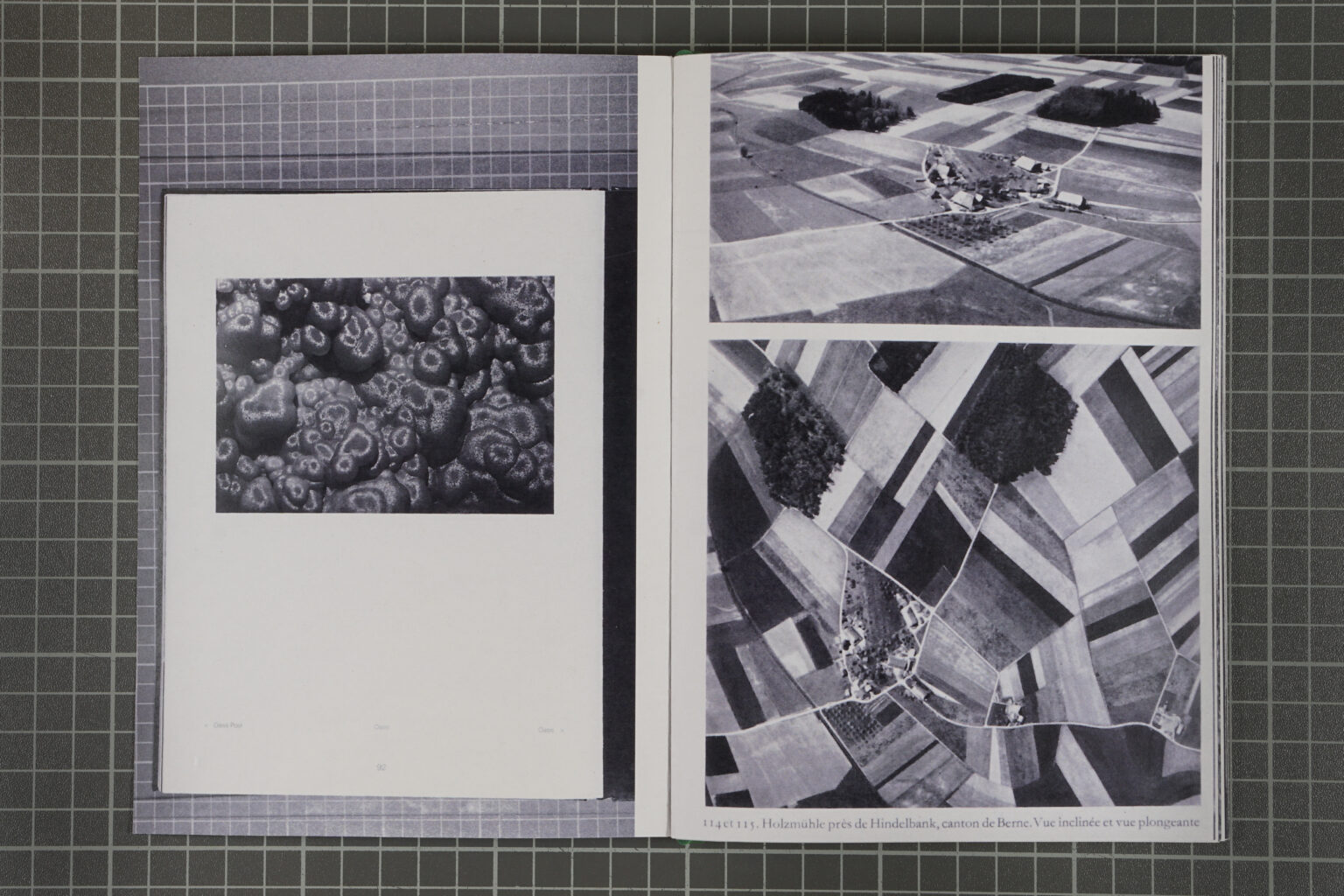

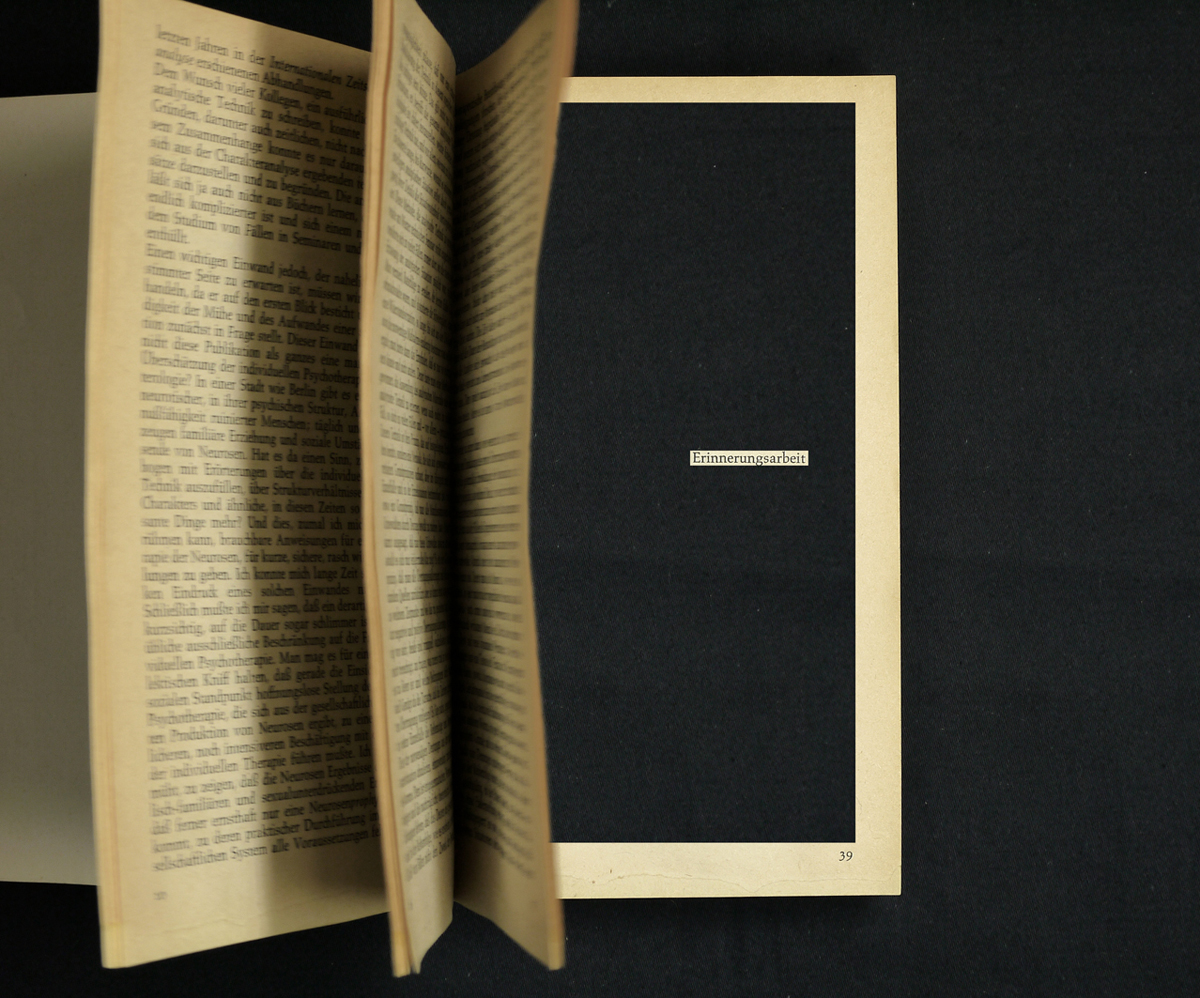

I initially intended to come to the Alpenhof to learn more about their peers — to spend time thinking about how the story of Kleenex/LiLiPUT related to the story of Peter Fischli, Livio Piatti, Bice Curiger, Erna Krips and more, to understand how they fit into the picture of Zurich-counter culture of the moment, at a place where the student movement, women’s lib, the F&F art school, and punk rock met. I was supposed to visit in March 2020, at which point I was at a very different, research-based stage of my project and we were in a very different stage of life on earth! Two years later, I spent my time at the Alpenhof thinking instead about the materiality of the book and preparing it for publication — what should it look and feel like? How should these images talk to each other? How do we preserve the feeling of the original while updating and expanding it for the present day? What does it mean to make a book that feels grounded in history but still contemporary, specific yet timeless?

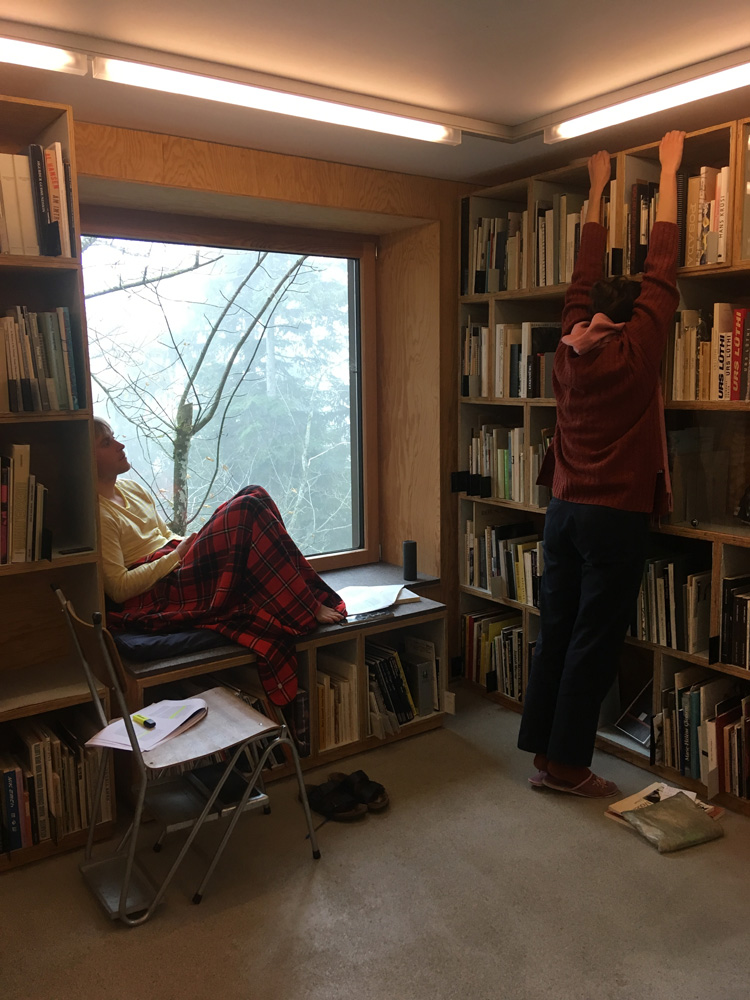

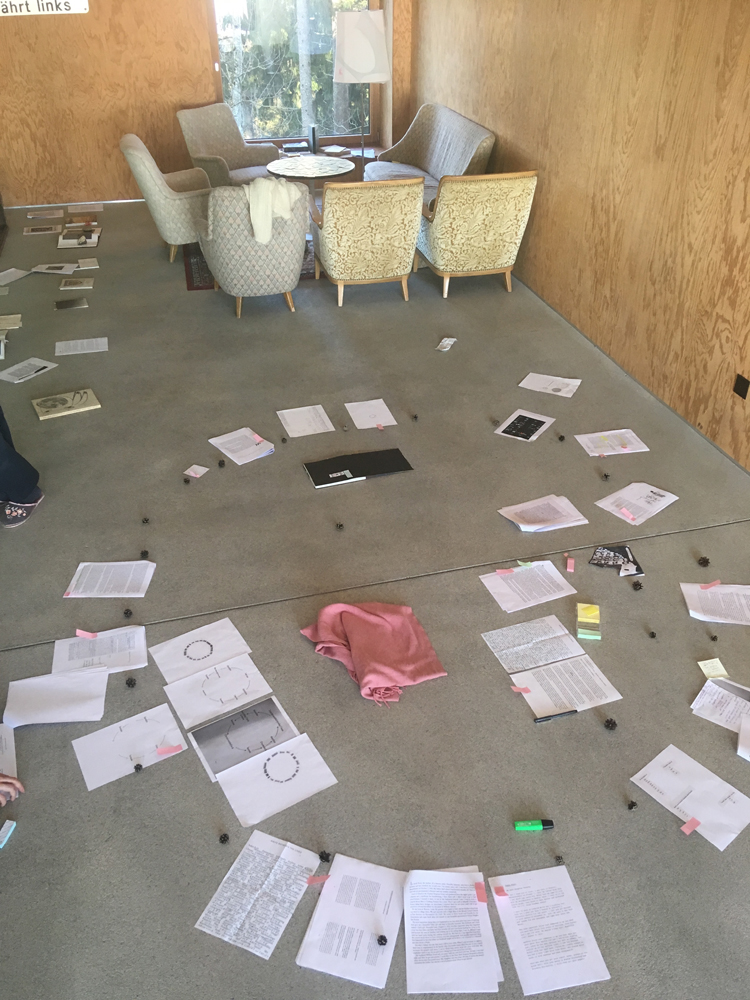

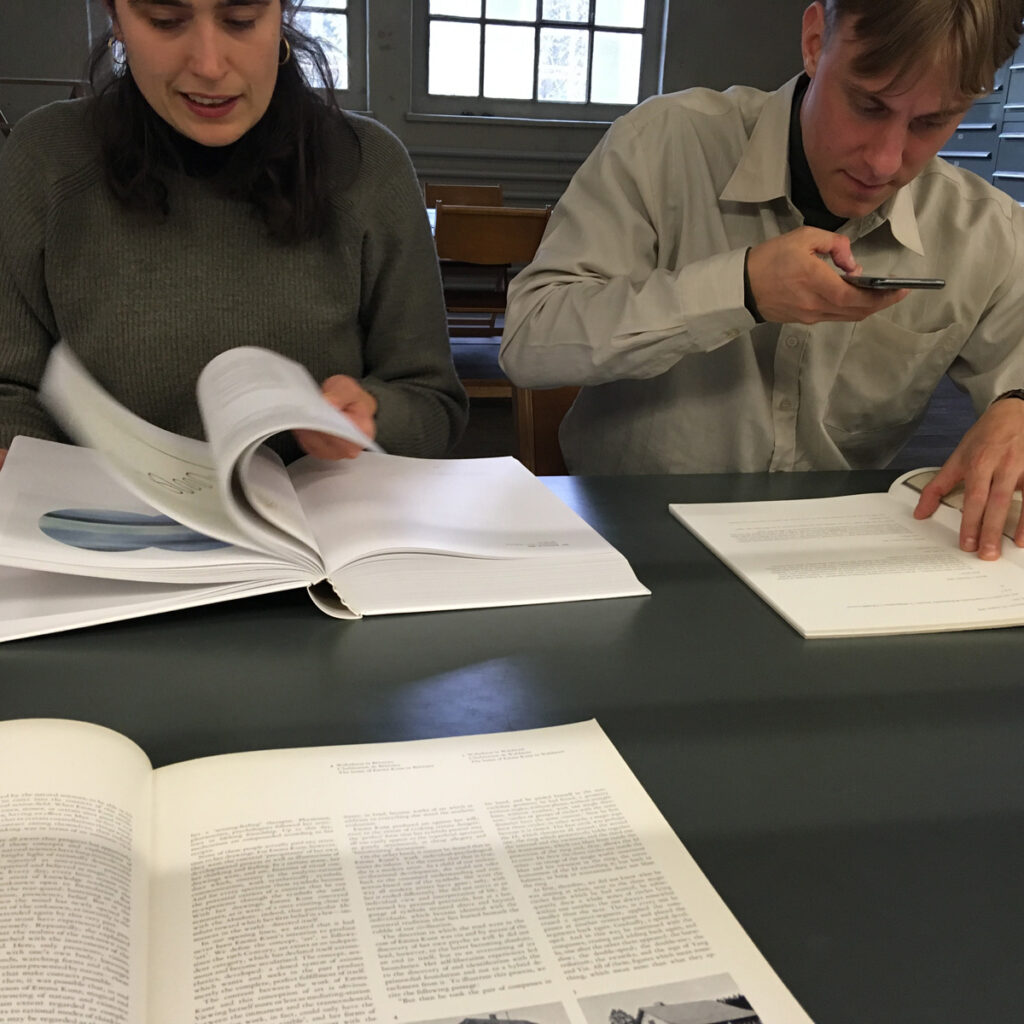

I explored books about Kleenex/LiLiPUT’s peers and predecessors, yes, but more than that I pulled books off the shelf and thought about how they felt in my hands. Where is the balance between readable text and a coffee table tome? Should the paper stock be coated or uncoated? How many pages feels just right? I worked with the designer, Conor Lumsden, who visited from Dublin and we spent days making infinitesimally small adjustments to layouts and pages, arguing about the tails on capital Q’s, and printing out and mocking up true-to-size versions of book spreads, looking at them, living with them and floating them past my fellow residents until we landed on something just right. A screen is no substitute for the real thing!

My time at the Alpenhof allowed me to approach the end of this project with the single-minded focus required to sort through hundreds of images and thousand words and the time I needed to puzzle through some of the text’s challenges. Plus, it was fun! Shared meals, long walks, and a late night dance party to Andreas Züst’s record collection… the highlight of which was of course singles by the forever-cool Swiss fräuleinwunderpunks, Kleenex/LiLiPUT. I look forward to sharing their story, reframed and reexamined, with the world soon.

Text: Grace Ambrose

April 2022

Ein Regal voller Geschichten aus meiner Perspektive,

und mein Begehren nach Geschichten.

Geschichten die schon lange Bilder in meinem Kopf sind,

festgeschrieben und stetig wiederholt.

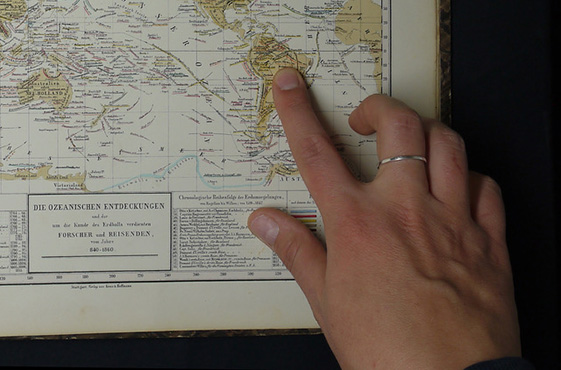

Ein Regal verstaubt und vergilbt, voller Begehren nach Entdeckungen, voller Lust der Entdecker.

Menschen, Kultur, Landschaft – Fische, Steine, Säugetiere, Insekten, Pflanzen, Geologie, Physiognomie und das Wetter.

Sammeln, entdecken, erfassen, erforschen, vermessen, kartografieren, beschreiben, aufschreiben, usw.

Im Online-Katalog werden zum Begriff “postkolonial” (0 Bücher gefunden), zum Begriff “Feminismus” übrigens auch. Dafür gibt es das Schlagwort “Das Weib”.

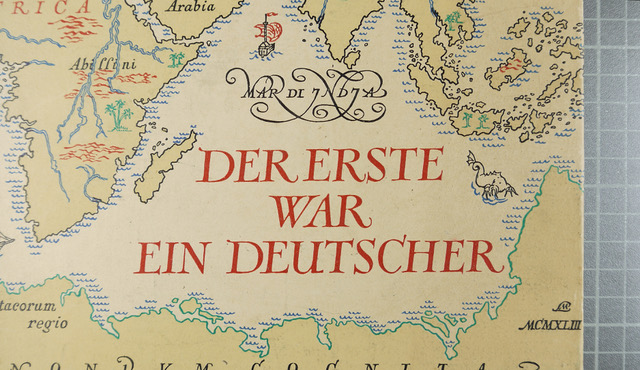

Ich frage mich, was ich hier mache, in diesem Eldorado der Erzählungen. Große Erzählungen:

“Afrika und die Afrikaner”

“Von Pol zu Pol”

“Auf Großer Fahrt”

“Von Peking nach Moskau”

“Das Bordbuch”

“Das Überseeische Deutschland”

“Die Deutsche Emin Pascha Expedition”

Jean de Lery, Humboldt, Kolumbus, Cook, usw.

Les Guides Bleus Illustrés, ein Reiseführer aus dem Jahr 1958. Von Paris nach Brazzaville (mit AIR FRANCE über Marseille, Fort-Land und Bangui) oder von Brüssel nach Léopoldville (über Genf und Tripoli) mit Karten und Abbildungen von den Denkmälern von König Albert I. und Henri Morton Stanley auf S.53, dazu Wasserfälle und Krokodile.

Durch die Mongolei,

nach China,

durch Brasilien,

zu den Feuerland-I* und zurück,

das Erklimmen von Berggipfeln,

Bilder von Wasserfällen,

Reisen zu Gletschern,

viele Strapazen und viele Entdeckungen.

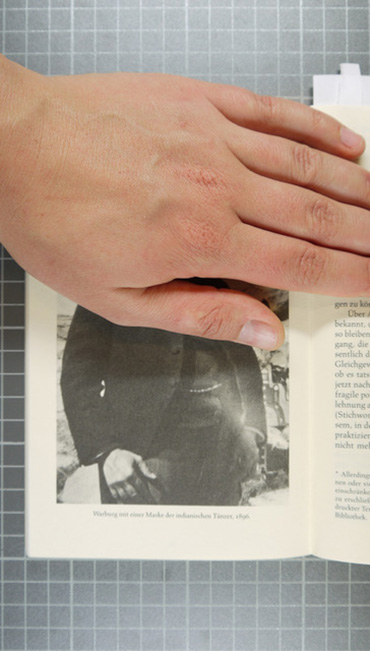

Geschichten von Vielen, die die Ersten waren und davon berichten. Dazu nehme ich die zweibändige “Anleitung – zu wissenschaftlichen Beobachtungen auf Reisen in Einzel- und Abhandlungen” von 1906 zur Hand. Hier werden die Weltreisenden aufgefordert zu dokumentieren und zu erfassen, was sie zerstören. Wissen ist Macht steht da ganz unverhohlen, denn es geht um die Erschließung neuer Märkte. Schon immer, nur war mir das nicht klar, da ich an der Oberfläche der Geschichten klebte.

Ein Regal in dem sich diese eine und meine Perspektive kristallisiert. Bücher die ich nicht mehr lesen will, mich aber frage, wie ich mit ihnen umgehen kann. Denn da stehen sie. Sie stehen da immer noch und bewegen sich nicht weg aus all den Bibliotheksregalen. Gedruckt ist gedruckt und ich bin nicht die Erste, die sich die Frage stellt was ich mit diesem Regal anfangen soll. Beim Durchforsten der Regalbretter und Durchschauen der Bücher fallen mir kleine und große handgeschriebene Zettel in die Hände. Auf ihnen haben die Künstler:innen Luisa Marinho und Miro Spinelli[1] postkoloniale Ansätze etwa von Grada Kilomba oder Suely Rolnik als Reaktion auf die in diesem Regal dominante Perspektive aufgeschrieben. Eine subtile Einschreibung in die eurozentrische Perspektive und ich überlege, ob nicht alle Bücher ein Glossar problematischer Begriffe, eine Kontextualisierung, eine Triggerwarnung vor gewaltvollen Bildern und Texten benötigen. Aber was mache ich jetzt mit diesen Büchern, die ich gar nicht mehr lesen und auch nicht bearbeiten will? Sie einfach im Regal ruhen lassen, gezielt an ihnen vorbei greifen, als nicht mehr adäquate Literatur?

Mit Laurence und Mirjam[2] diskutiere ich am Abend den Zusammenhang zwischen meinen Überlegungen zu den kolonialen Reiseberichten und der 2018 erschienen und kommentierten Neuausgabe von “Mein Kampf“ – das hier im Original im Regal steht.

Dieser Text entstand am 22. November 2020, an meinem letzten Tag in der Residency Bibliothek Andreas Züst. Im September 2021 habe ich die Fußnoten eingefügt und im April 2022 habe ich den Text noch einmal gelesen und gekürzt.

[1] Luisa Marinho und Miro Spinelli waren im November 2017 in der Residency Bibliothek Andreas Züst.

[2] Die Dokumentarfilmemacher:innen Laurence Favre um Mirjam Landolt waren zeitgleich im November 2020 in der Residency Bibliothek Andreas Züst und wir haben viele Mahlzeiten und Überlegungen in dieser Zeit miteinander geteilt.

Text: Frauke Zabel

November 2020/April 2022

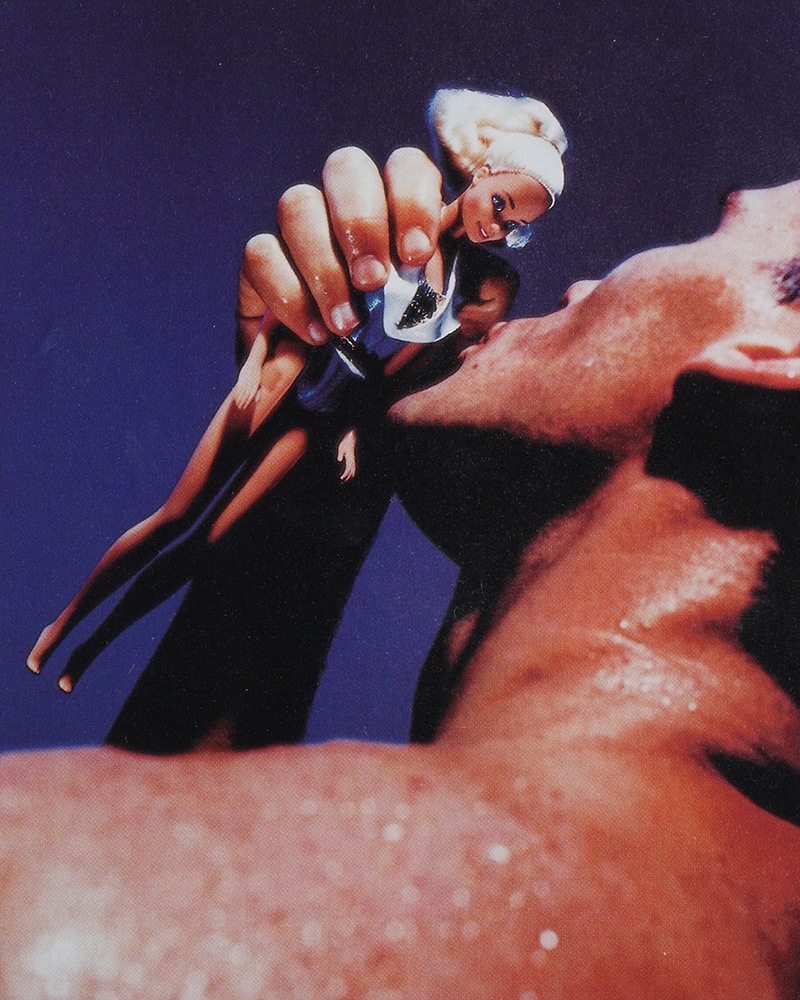

Männerphantasien

Anthropologist Anna Tsing talks about “hope” in an interview, saying that “in arts, humanities and sciences we got hooked on hope and we wanted to believe in our creative possibilities. An ungrounded optimism which suggested that we didn’t have to worry.” Citing Donna Harraway, she says that her way of telling stories of terrible things aims to make listeners “stay with the trouble”: “to engage with the kinds of problems they were involved in rather than running away from them.”

Thinking about contemporary art today, “hope” is very much expected everywhere, even though we are at a place where “nothing would grow”, we are expected to create something which warms us up or gives us a light of the possibility of growing out of this much stronger. It even implies the one direction road, which is “the growth”, further and better.

Looking at the archives of Andreas Züst, while you get lost in the 20th century, you also get a bit closer to the burning core of our life in the 2020s, like you are walking towards the center of a power plant.

Autobahn

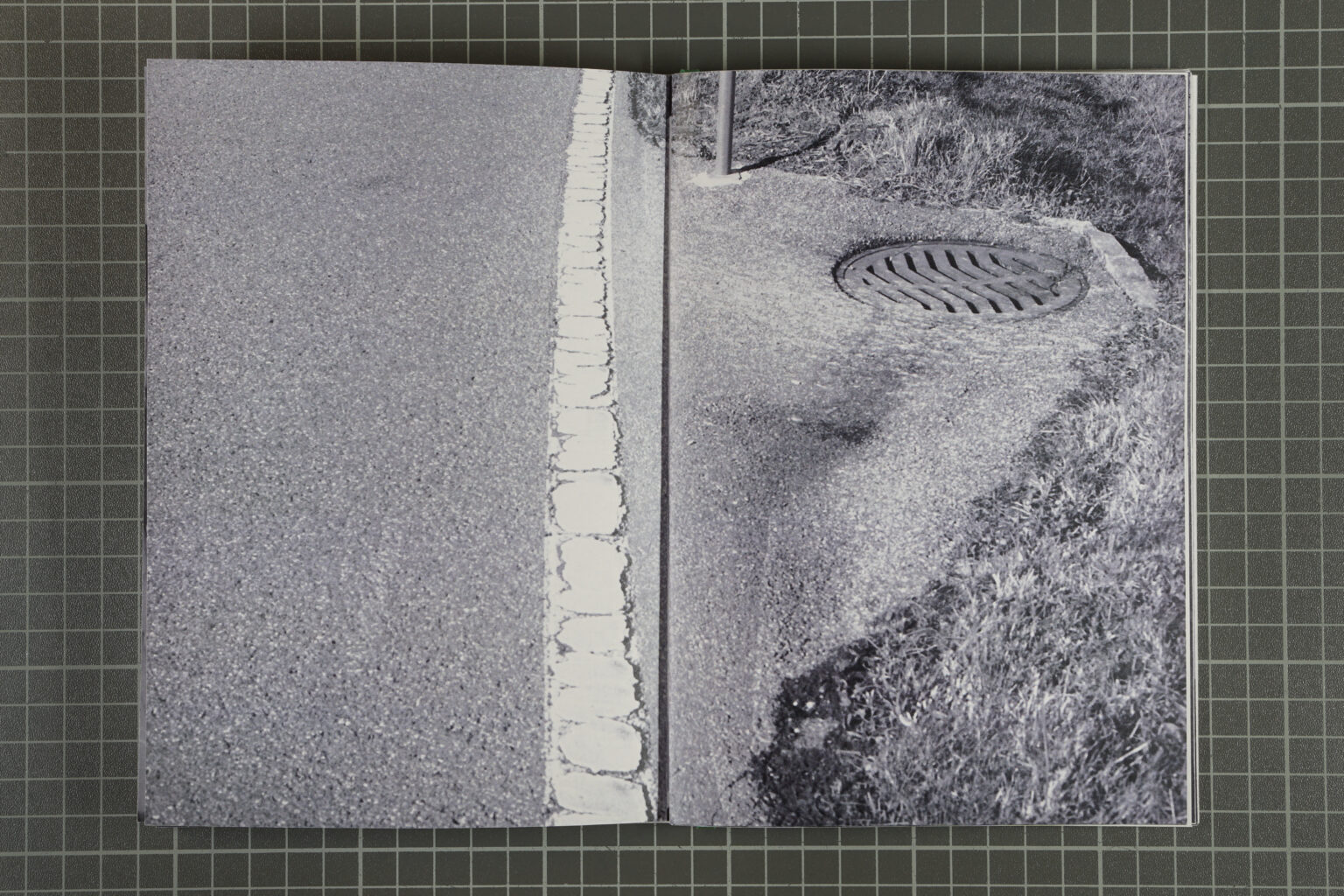

Once you get out of Alpenhof you find yourself on an asphalt road and you have to claim it for yourself as a pedestrian to go anywhere. It is the only way to walk in the area other than the small semi-public paths that circle around private properties, unless you don’t want to go into the woods.

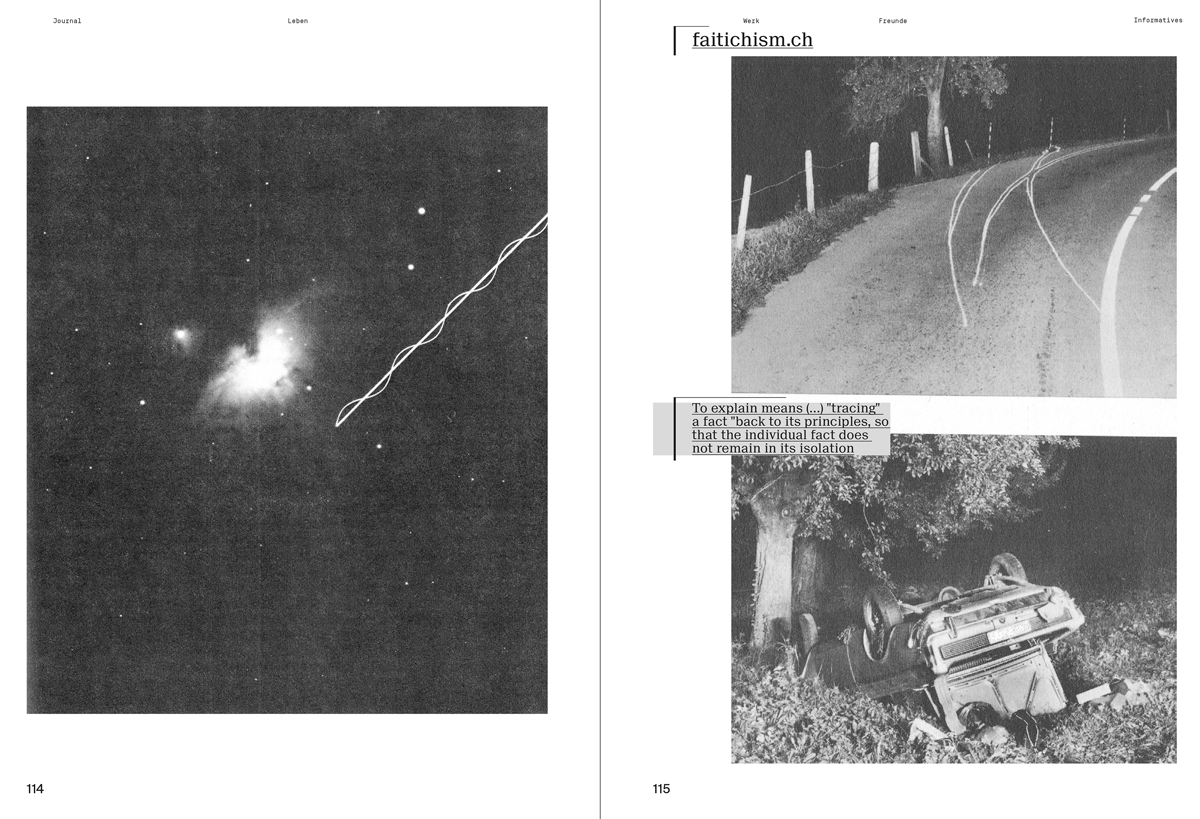

In the library, when reading the book Die Schweizer Autobahn, I am being told about different layers of asphalt; 1m thick asphalt sticking to people’s feet and the house facades in the early days of asphalt, different catastrophe phantasies and asphalt as an escape tool governments used to promote highways, asphalt as a means of preventing uprisings and to control, asphalt as a propaganda instrument and an embodiment of ‘beauty and nation’ in the NS era of Germany, asphalt as a tool to turn the nature into resorts for city dwellers in the US and Switzerland, and asphalt building as a charity activity for getting closer to god.

Although rural areas in Switzerland like where the library is are mostly surrounded by asphalt roads and highways, I could find just a handful of books on them in the collection. Maybe the method of finding an unknown subject and transforming it into a knowable with a certain anthropocentrism is less applicable, in this case, than to other subjects such as sky, cosmos, seas or UFOs, on which you find plenty of books in the library. For the subject to be transformed into a more knowable, it should appear first as an unknown. When this unknown status stands in contrast with the stable circumstances in which one lives, it gives them a certain confirmation of their security. Similar to how horror films satisfy people.

Männerphantasien

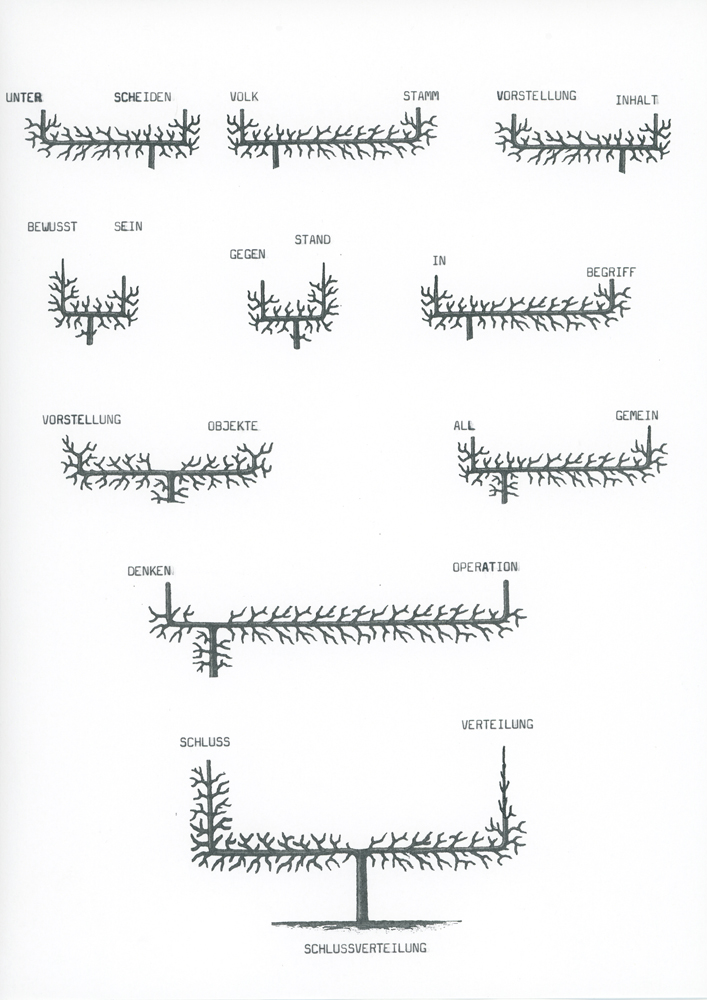

Historically in many sciences, not unlike the fields of anthropology, geology and cosmology, the cultural perception of the scientist is very much shaped by a gendered understanding of that figure, who inhabits qualities that are traditionally attached to masculinity. These qualities assume that masculinity is somehow naturally connected to certain types of curiosities that are often utilized for the advancement of all humanity. These individualist versions of masculinities share a commonness when looking at the stars, or climbing on top of a high mountain; cataloging outer space objects, as well as plants and animals.

When going through various catalogs of meteoroids and other space objects at the library, one can also wonder about the fundamental connections between masculinity and humanism that are naturally embedded in the history of cosmology. As cosmologist Chanda Prescod-Weinstein points out, back in the 20th century many men in the scientific community were driven by the sense of individual success, but the ways of the “olden days” are still not much changed. Looking at the stars, and in general, exploring outer space are still fueled by the narratives of “carrying the torch of humanity” type of individualist génie spirit.

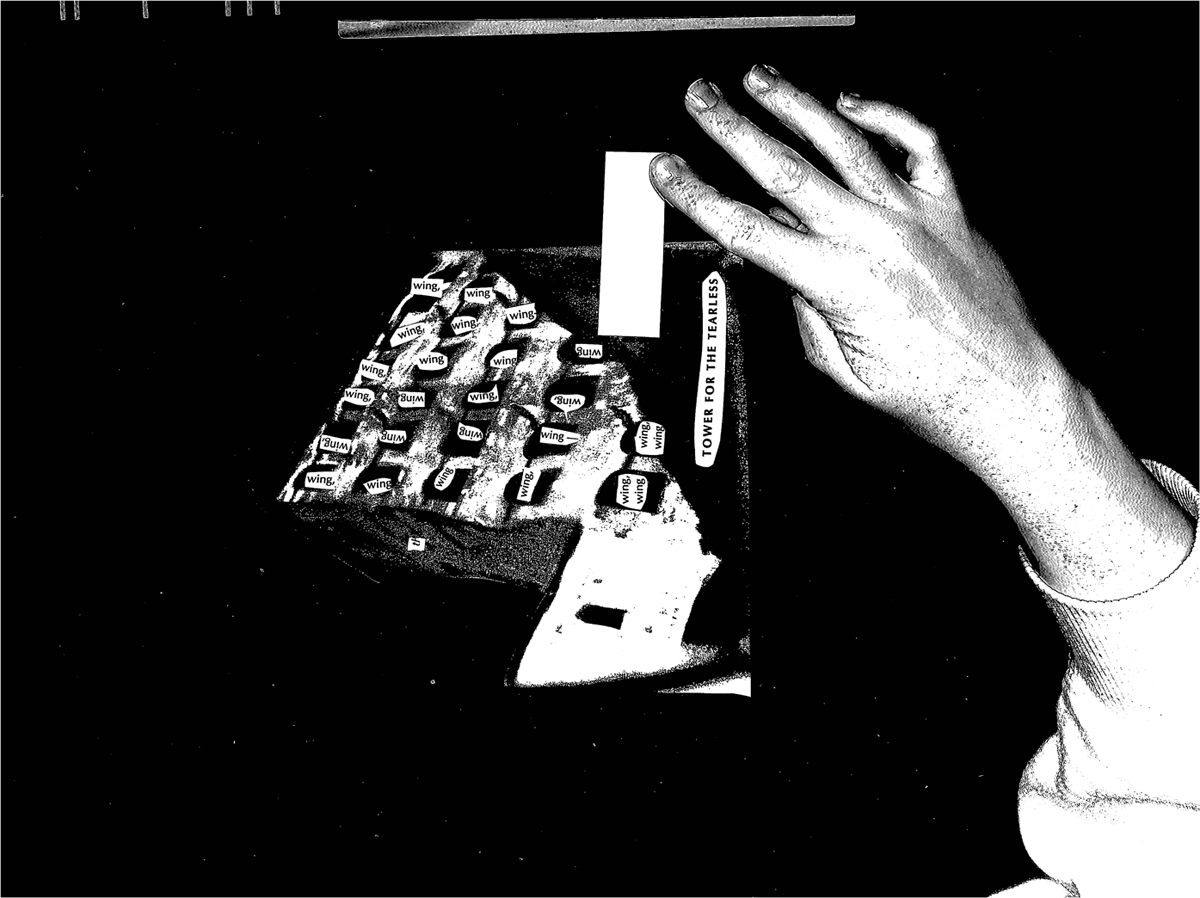

Autobahn, Meteoriden, Höhlen, Männerphantasien, Documenta 2 is a zine we worked on during the residency at Bibliothek Andreas Züst, made with the materials we found in the library. It will be published by Well Gedacht Publishing in April 2022.

Text: Eren İleri, İpek Burçak

November 2021

Within this residency, the building’s space and functions organization constituted my exploratory foci. I was interested in Andreas Züst residency building, not as an architectural object but more in investigating its internal functional system, individualizing elements like: space structure, social interaction’s rhythms, program and the different function’s relationships.

The entity brought together functions such as a library, a community room, private living spaces, a terrace, and services. While programmatically, it hosts an artistic residency, hotel rooms, public gatherings, workshops…etc. In some periods, all this functions can be operating at the same time.

Under this situation, processes like “transforming, “merging”, “juxtaposing”, “combining”, “hybridizing” are applied to the Andreas Züst residency’s functions. It was fascinating to experiment and to observe this “hybrid way of living” during my stay. I believe in architectures that have the capacity to change and adapt to different conditions and needs. Temporary architecture and temporary functions allows us to explore unknown territories: I believe that ephemeral goes far beyond the meaning of short duration, it triggers a semantic stratification processes that transform the space into a common place.

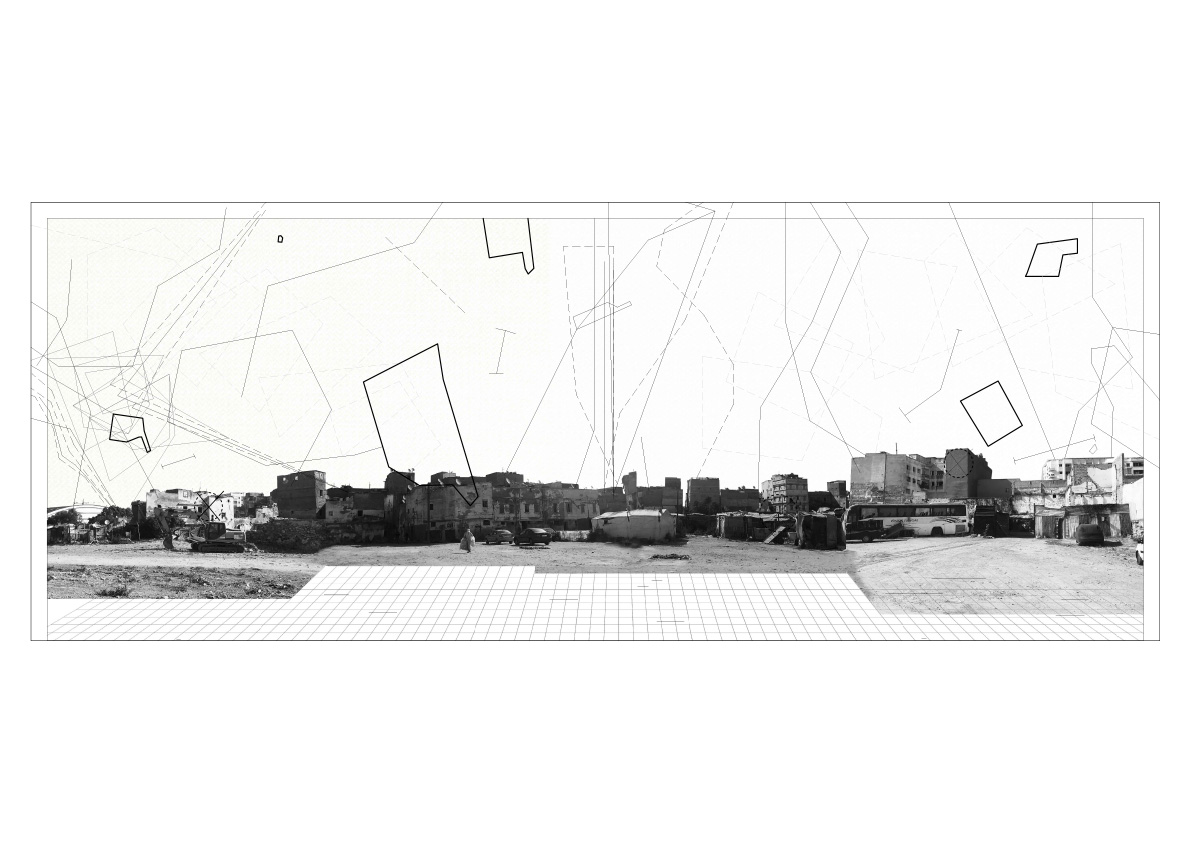

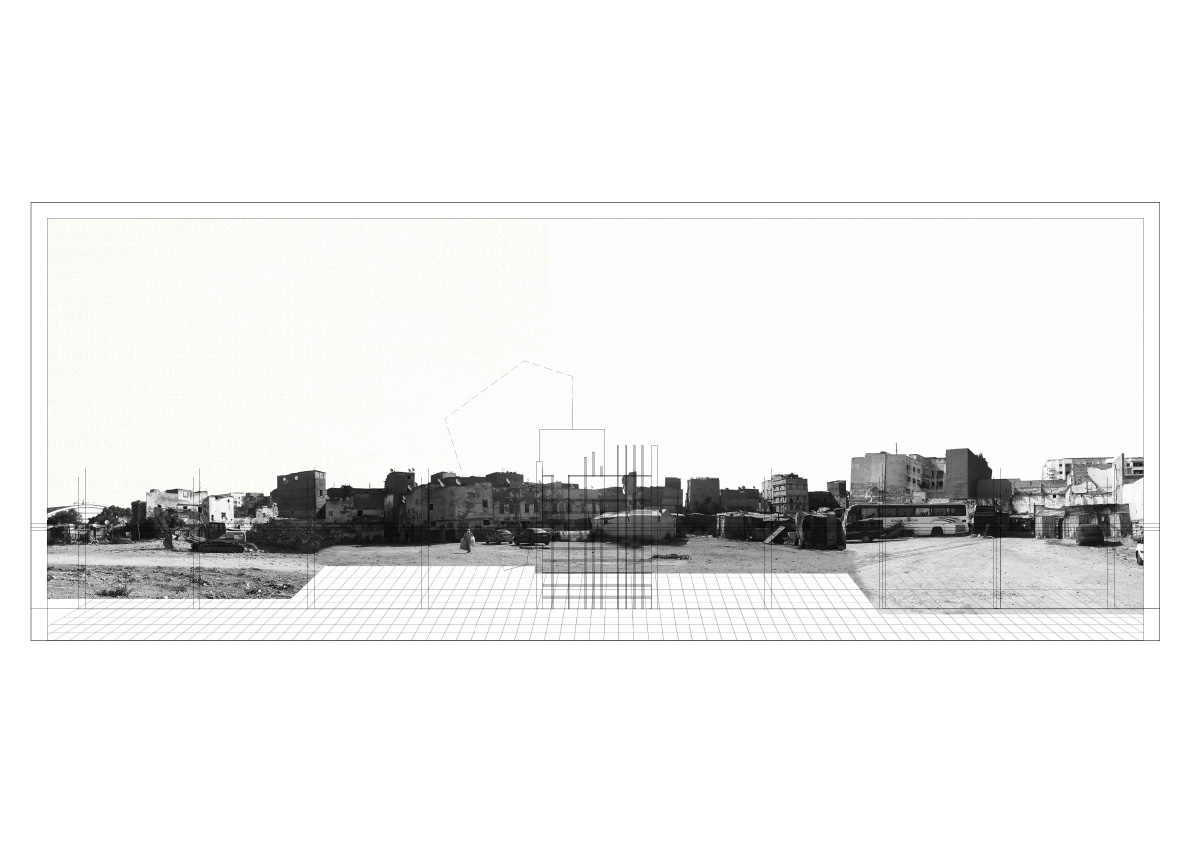

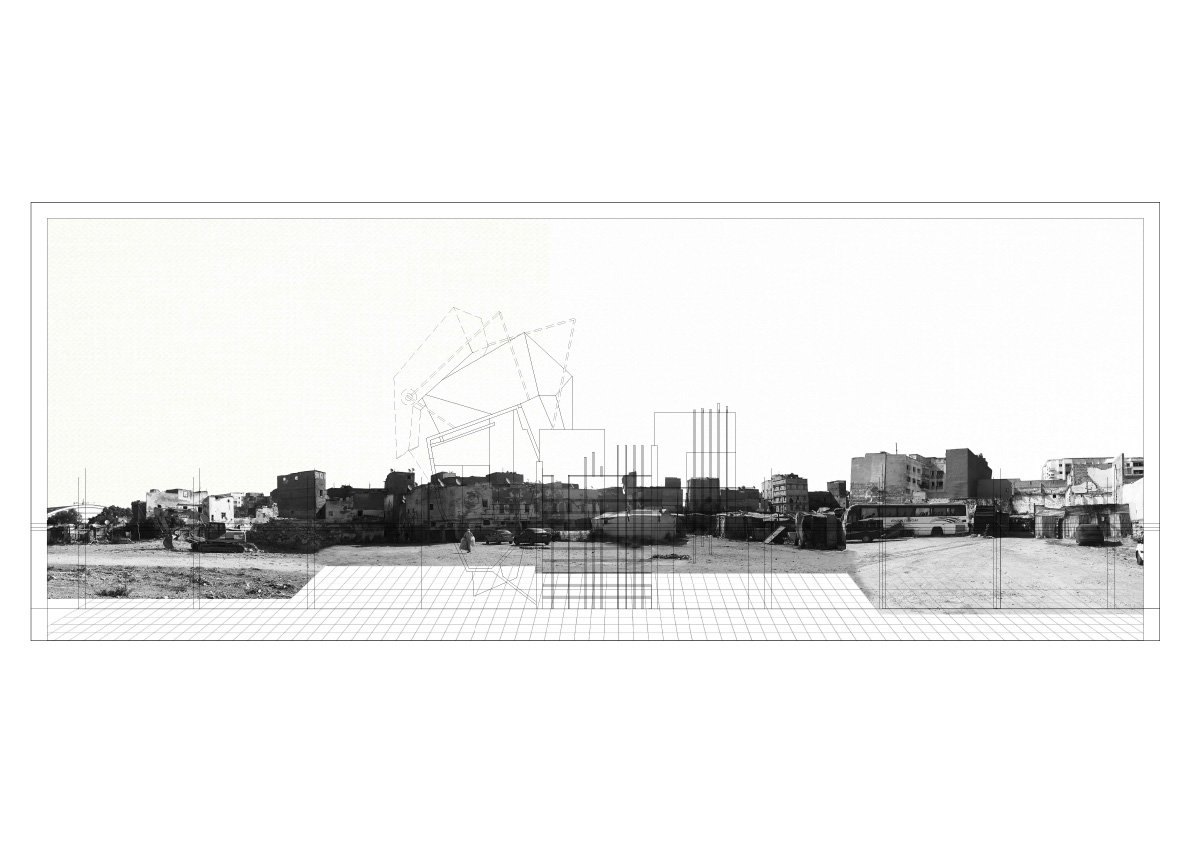

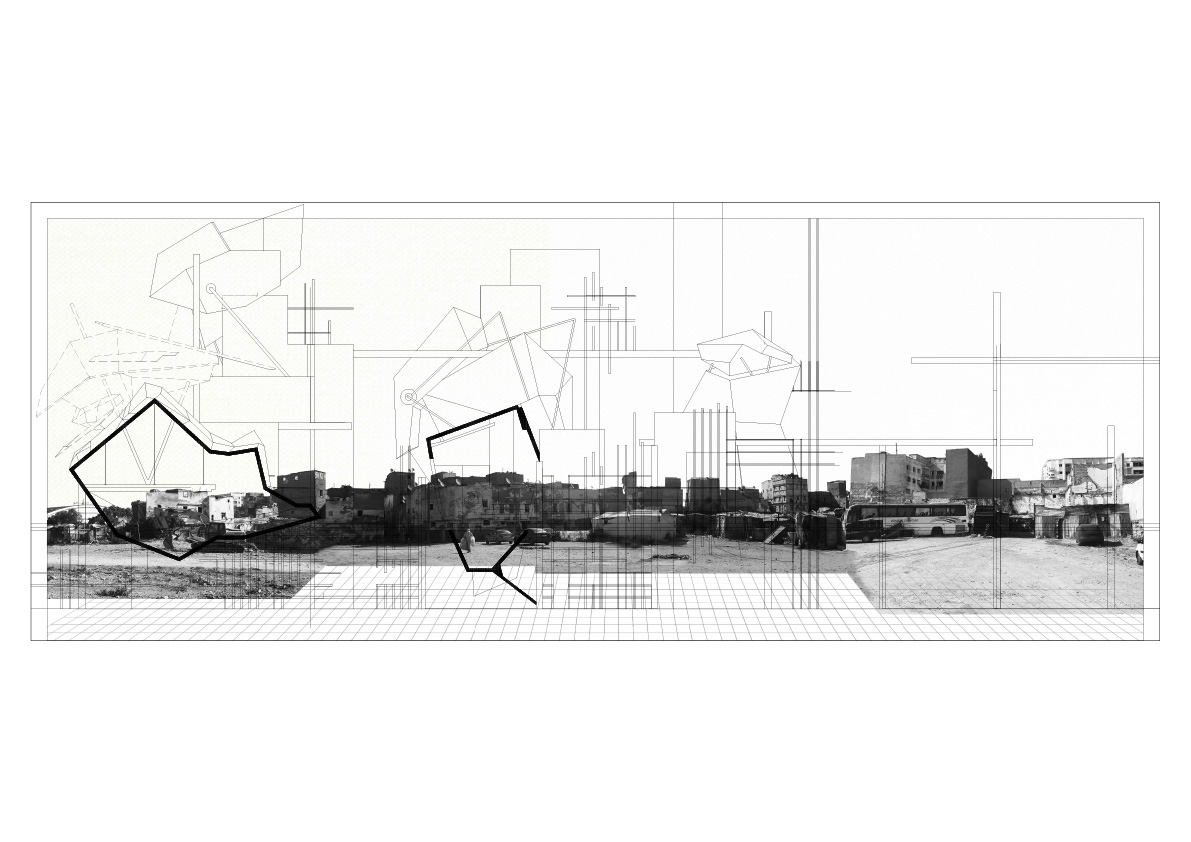

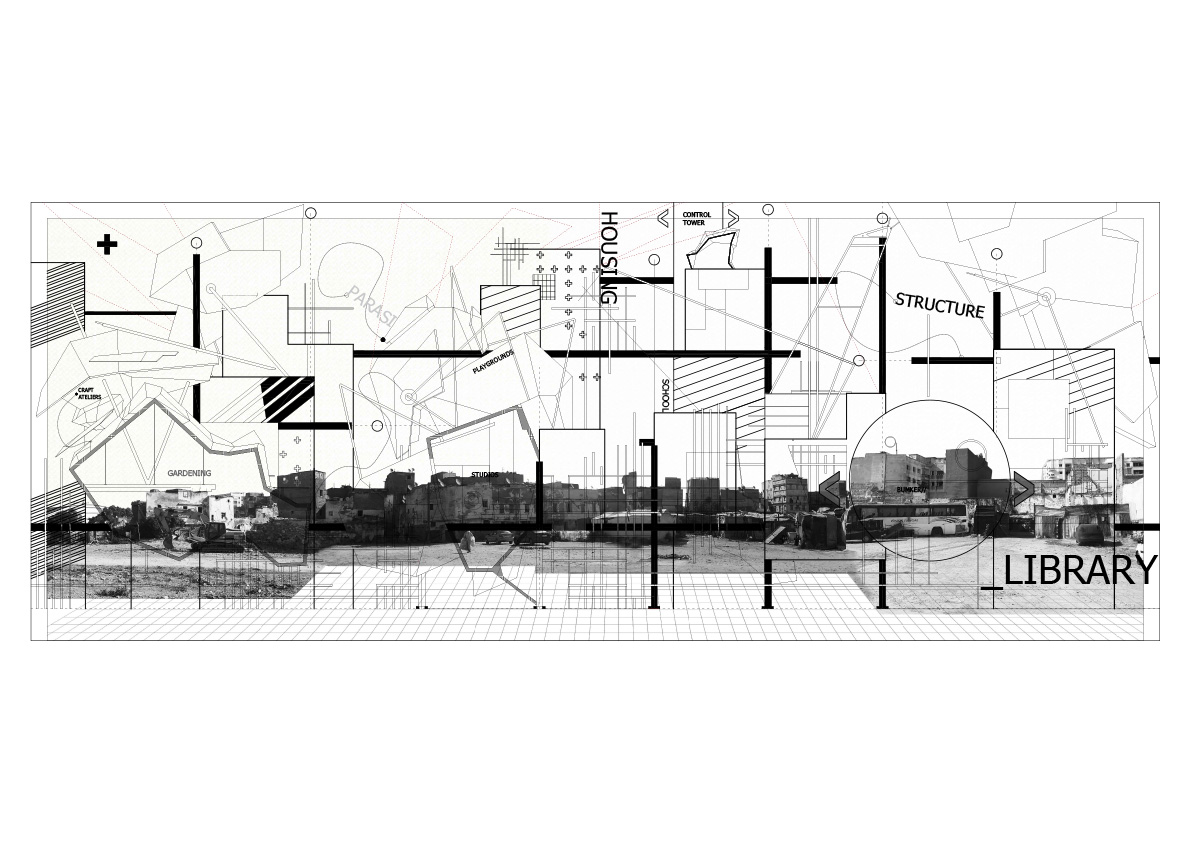

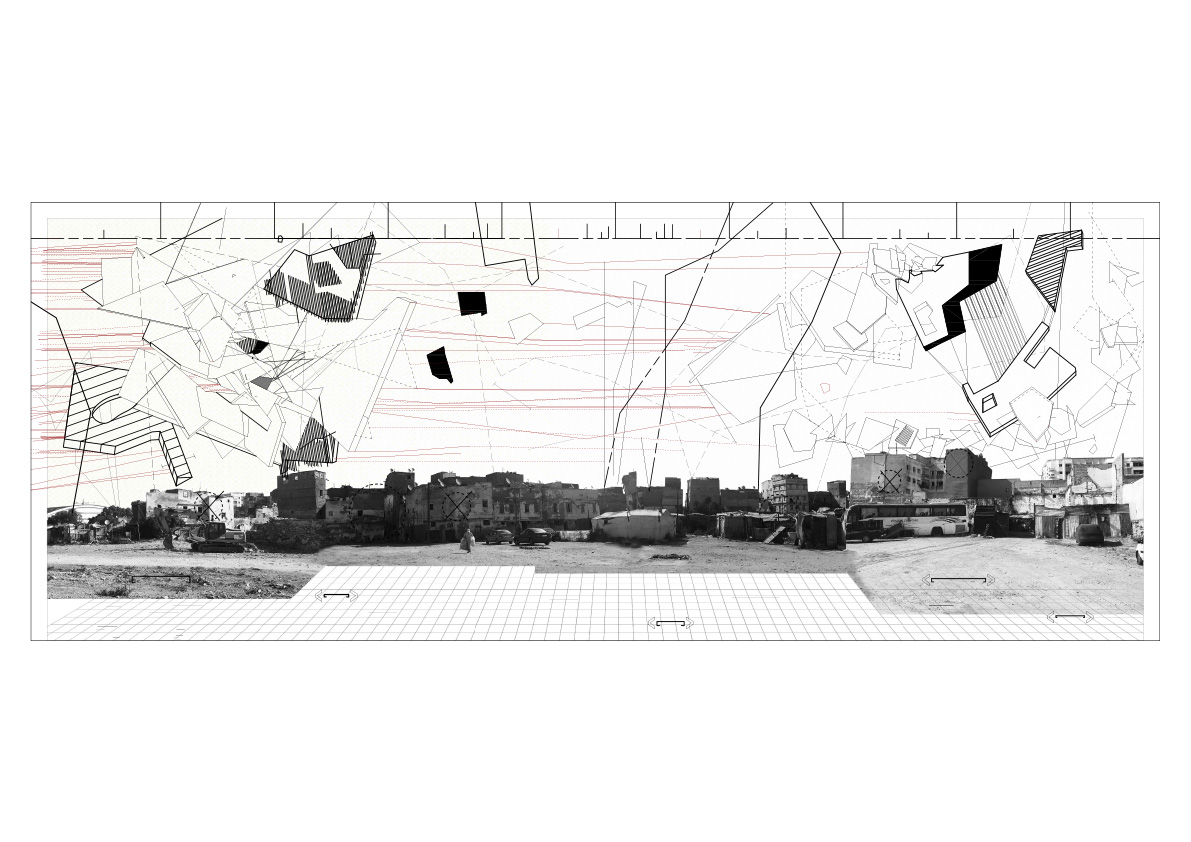

My project the library never die, explores and takes inspiration from all this processes , applied to a different context in Morocco, where usually libraries are monofunctional and non-permeable spaces.

The project is a peculiar library implemented in a vacant site in Casablanca’s old Medina, in a poor neighborhood. The aim of the library’s existence in this site is to constitute a primary structure to inject other functions (parasitical structure) that the population needs in an never ending transformation.

The result is mobile, unstable, provisional, and dynamic. Strange shapes that open-up uncovering instant squares, temporary structures that get reorganized according to specific needs. Some of these works arise on the same site where others just disappeared, giving birth to chains and creating spaces in progress, evolving, always uncompleted. They are, literally, «provisional constructions», built to supply a specific need and intended to be replaced by something else. At the same time, however, they are «provident constructions», able to see beyond their temporary utility and to imagine the place they occupy after their own disappearance.

Text: Fatim Benhamza

November 2021

For Daniel Lara Ballesteros and Rodrigo Toro Madrid, the residency meant the first collaboration between them, and an opportunity to join forces around topics that both had explored separately: randomness, and automatism.

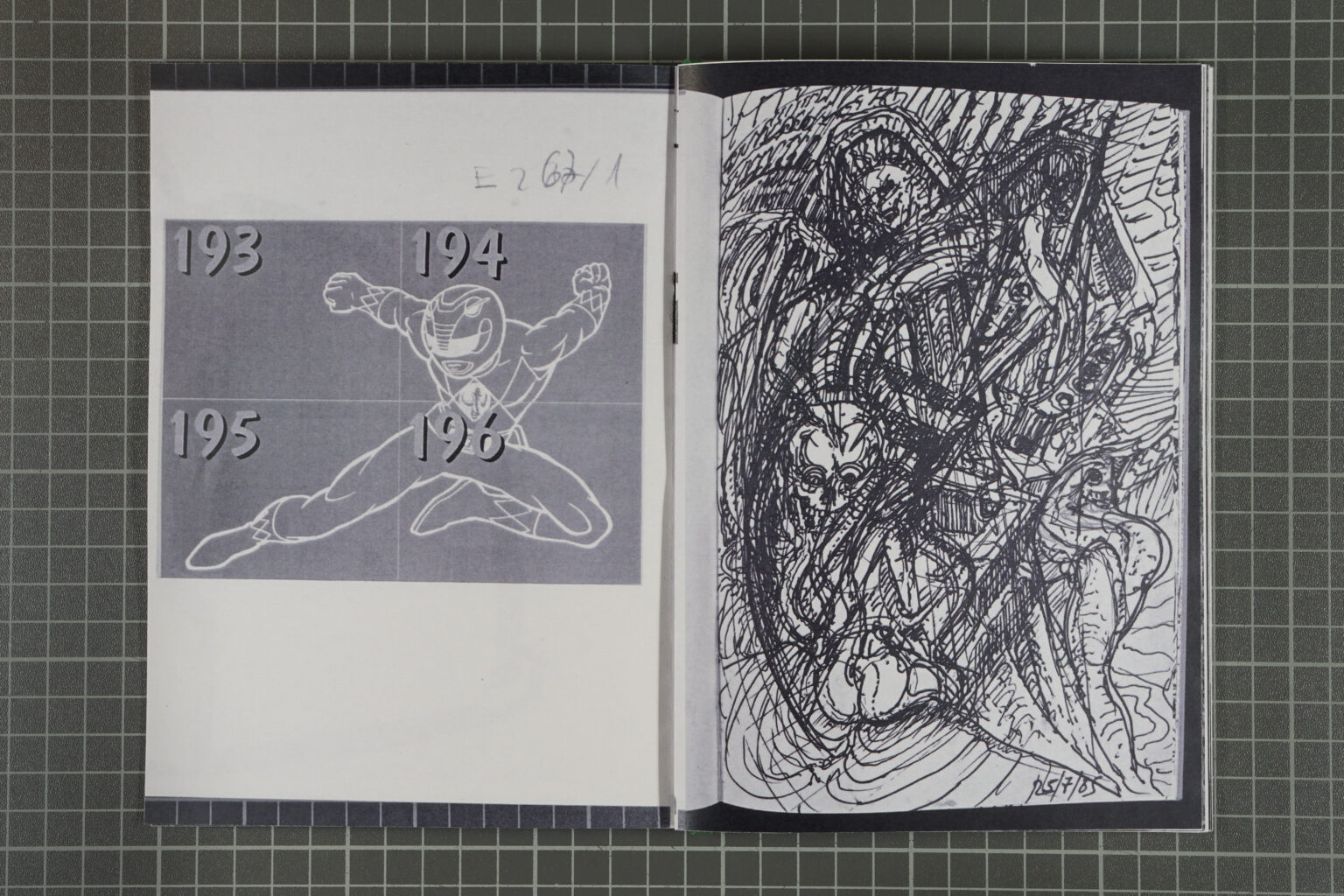

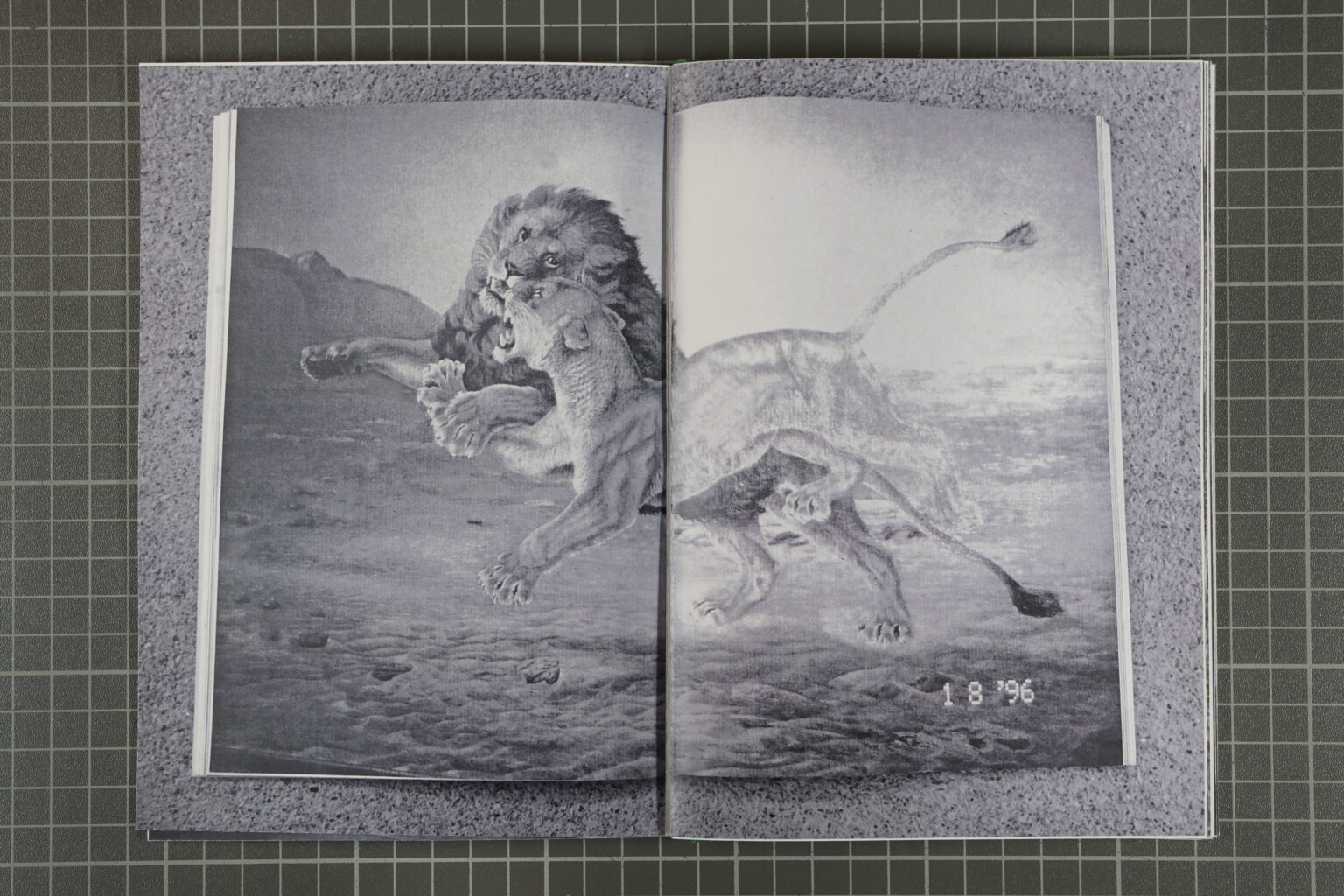

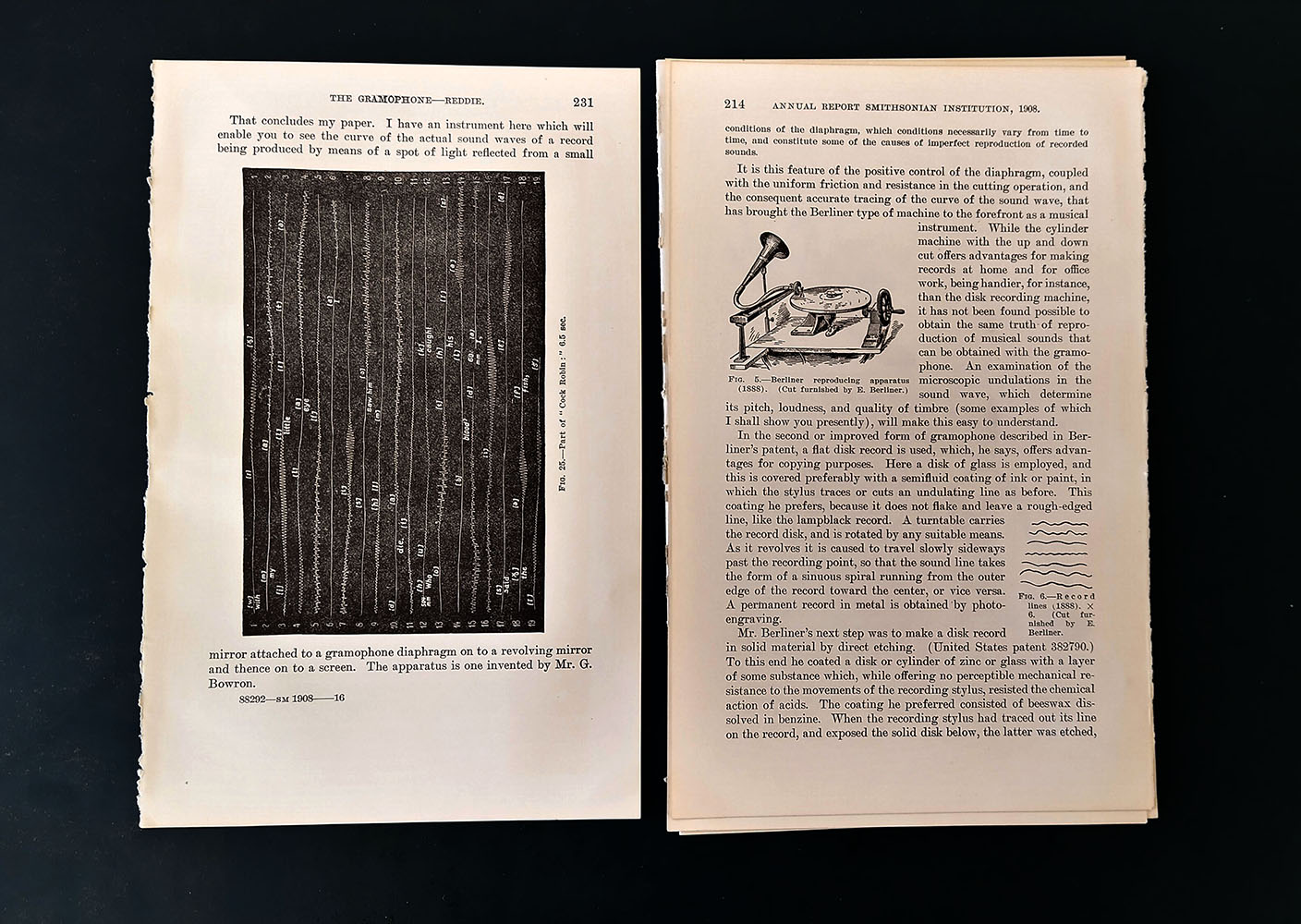

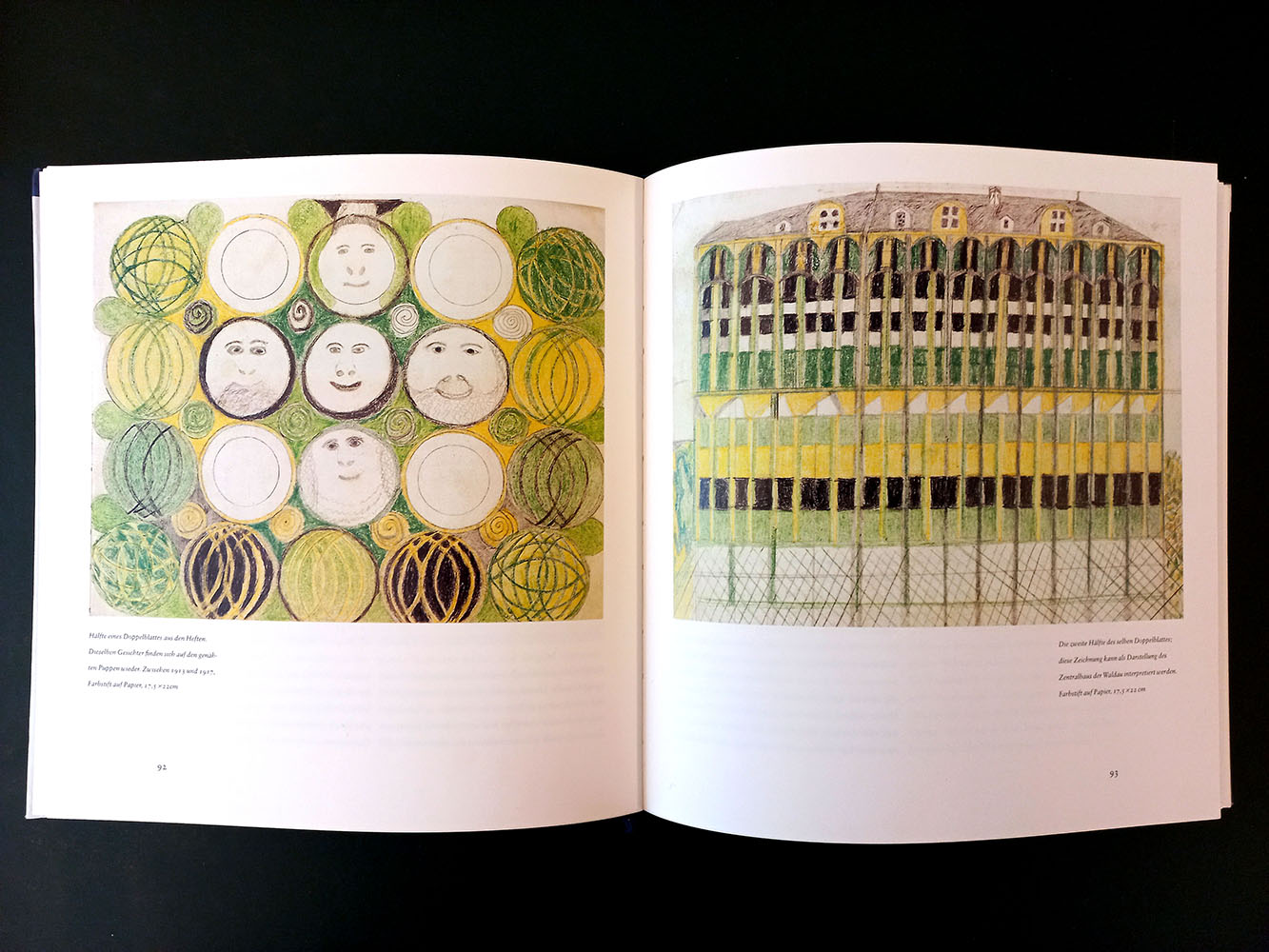

On the one hand, Daniel researched the selection of Art Brut books in the library to interpret the images and compose sound pieces by means of synthesizers and rhythm boxes. In his words “…from my subjective vision I tried to relate equivalences of colors to musical notes, line styles to sustain, tremolo, glissando or decay, the general composition of the drawing to rhythmic sequences or successions of notes and other relationships”.

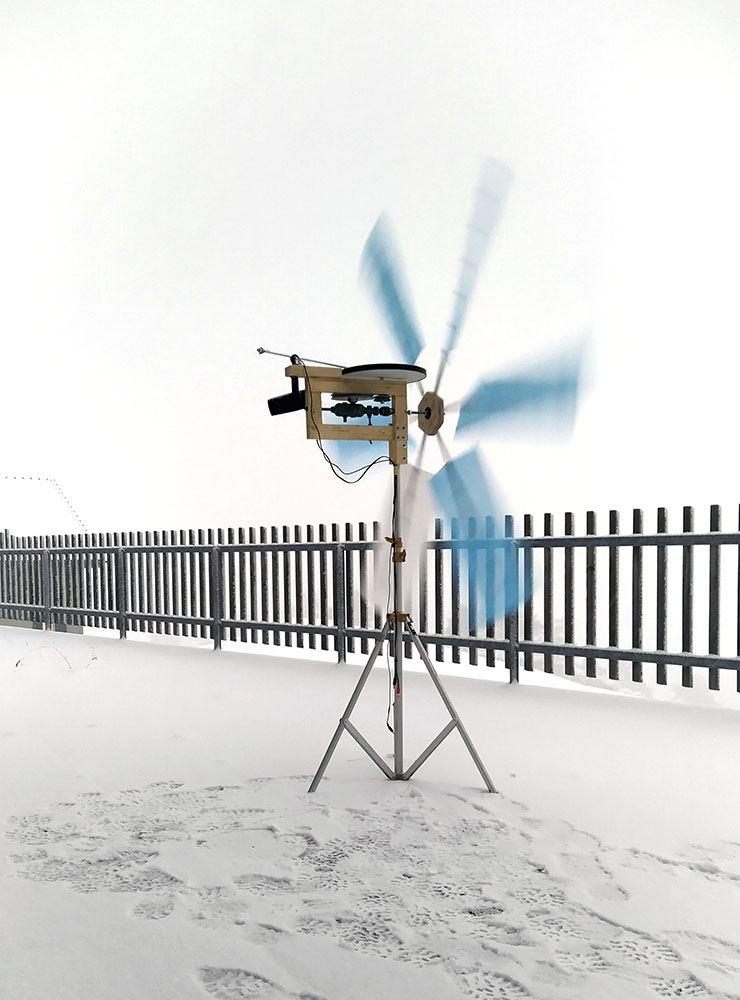

Rodrigo’s interest, on the other hand, lay in the characteristics of the landscape and the weather. He built a turntable activated by gusts of wind in the mountains, causing a sound reproduction always variable and unpredictable.

At the end of the residency the joint work “Wind Serendipity” was presented, which is a “site & time specific” experience, where a composition that can only be correctly reproduced under the influence of the wind is placed in the middle of the landscape to dialogue with the mountain and its invisible presences.

Text: Daniel Lara Ballesteros, Rodrigo Toro Madrid

November 2021

Weather, geology, shamans, aliens, kitsch, popular culture… All-too-human, the woman… The ‘precarious line between encyclopaedic understanding of the world’ and the arbitrariness of choices and passions made the library a fascinating collection to analyse, a modern ‘cabinet of curiosities’. We explored the collection and the ‘daring jumps’ between topics, the juxtapositions between serious and humorous, scientific and speculative. The library as a time capsule, representative of its time and location.

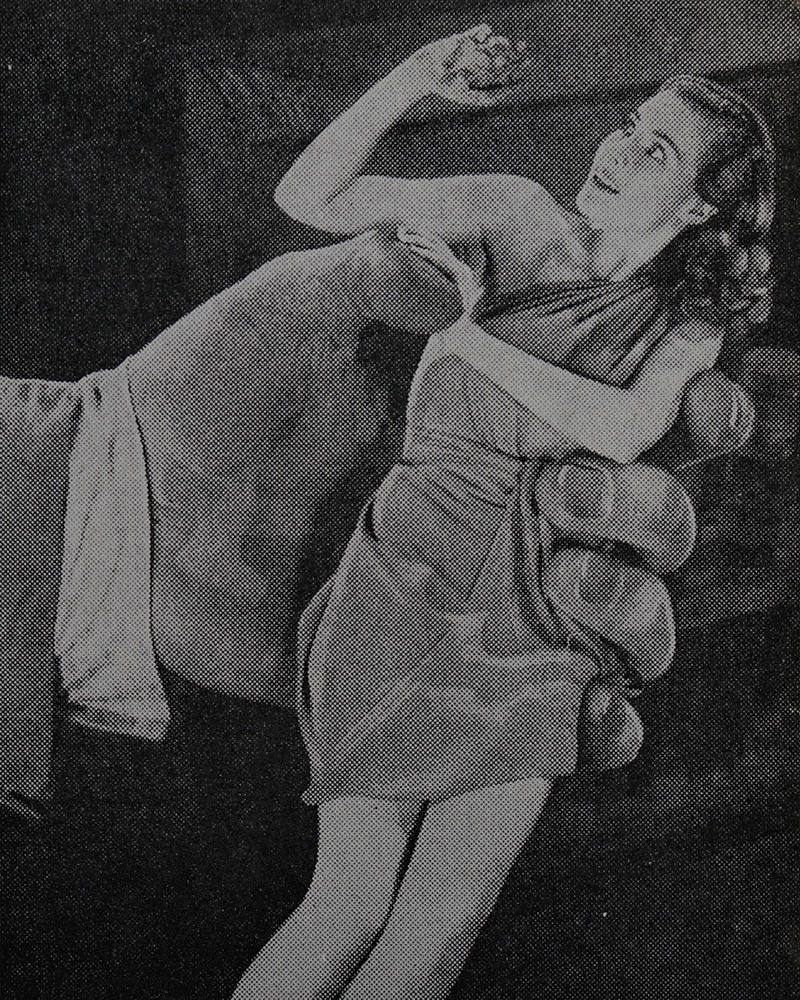

But what happens when rigid categories are shaken? When the way we are used to ‘read’ the world is questioned? The feeling of chaos, disorientation, discomfort, fear, often comes from shaking fixed perceptions. Disorientation is also one of the most widely used methods in horror films to create suspense. ‘(Dis)orient’ is a horror visual essay based on a vast variety of visual materials collected from the library, exploring how context, order and categories construct meaning and how systems of organisation dictate narratives.

Text: Daria Kiselva & Amir Avraham

November 2021

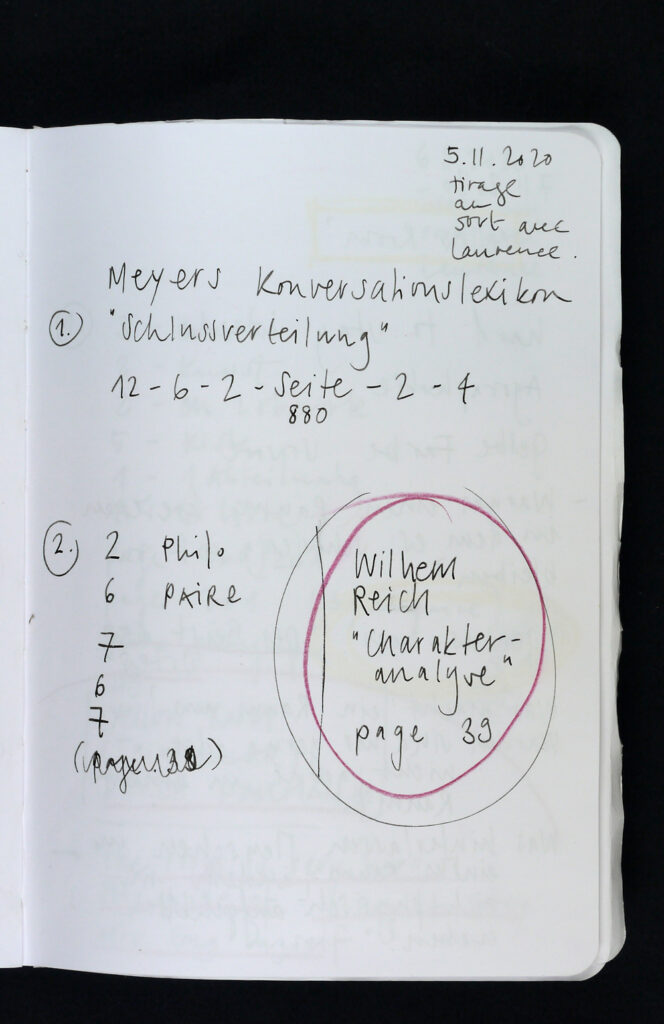

Au début étaient deux dès.

Et avec le jeux d’eux, le hasard.

Ou sans, s’il n’existe pas.

Mais, dans tous les cas,

une longue plongée

dans un océan de livres

au dessus de la mer des nuages.

De un à douze ils diront

Où aller, que regarder

De un à douze ils décideront

Un texte, une image

Point de départ aléatoire

Pour mieux s’ouvrir

Pour mieux se perdre

Point de départ aléatoire

dix-sept livres

ou seize, plus joker

au fur et à mesure

des liens de tissent

des nœuds se lient

des points d’interrogations restent

6-5-3-6-1

un garçon porte un sceau d’eau

il a dix ans en 1947

c’est une photo en noir et blanc

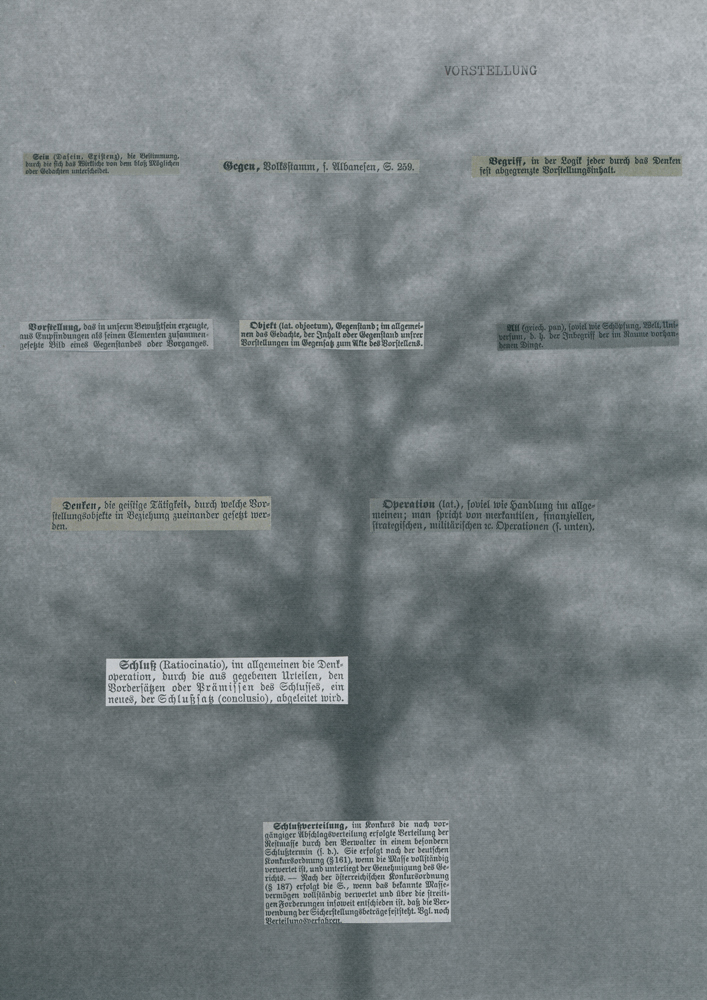

12-6-2-2-4

une encyclopédie du XIXème

installée en bas de l’escalier

crache un mot mystérieux

tout près de là;

die beschissene Restgruppe

si on lui tourne le dos

et qu’on porte son regard

vers là-haut

on voit des ovnis

et d’autres labyrinthes humains

Hasard provoqué, hasard subi

Apprivoisé, conscientisé, guidé

Charmante sorcellerie post-dada

En forme de légitimité du passé

À rester contemporain

Novembre 2020

Texte : Mirjam Landolt & Laurence Favre

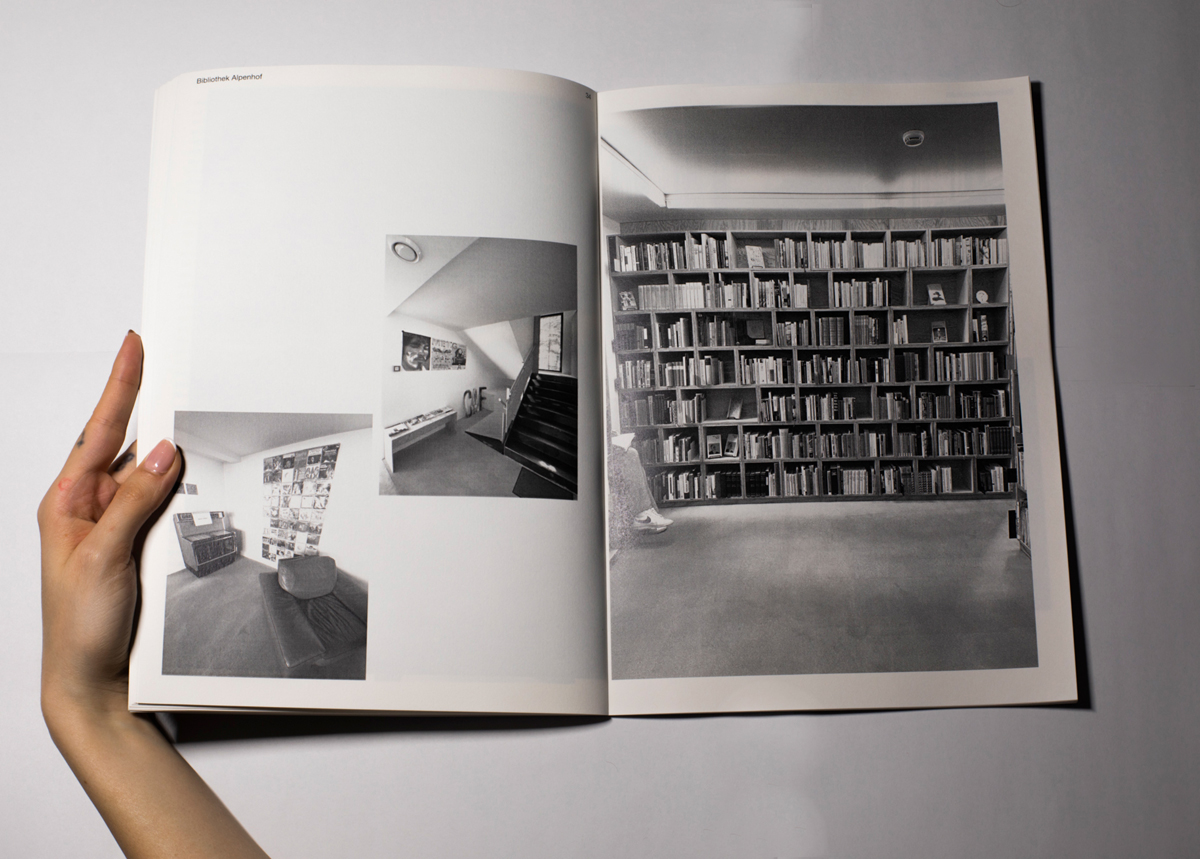

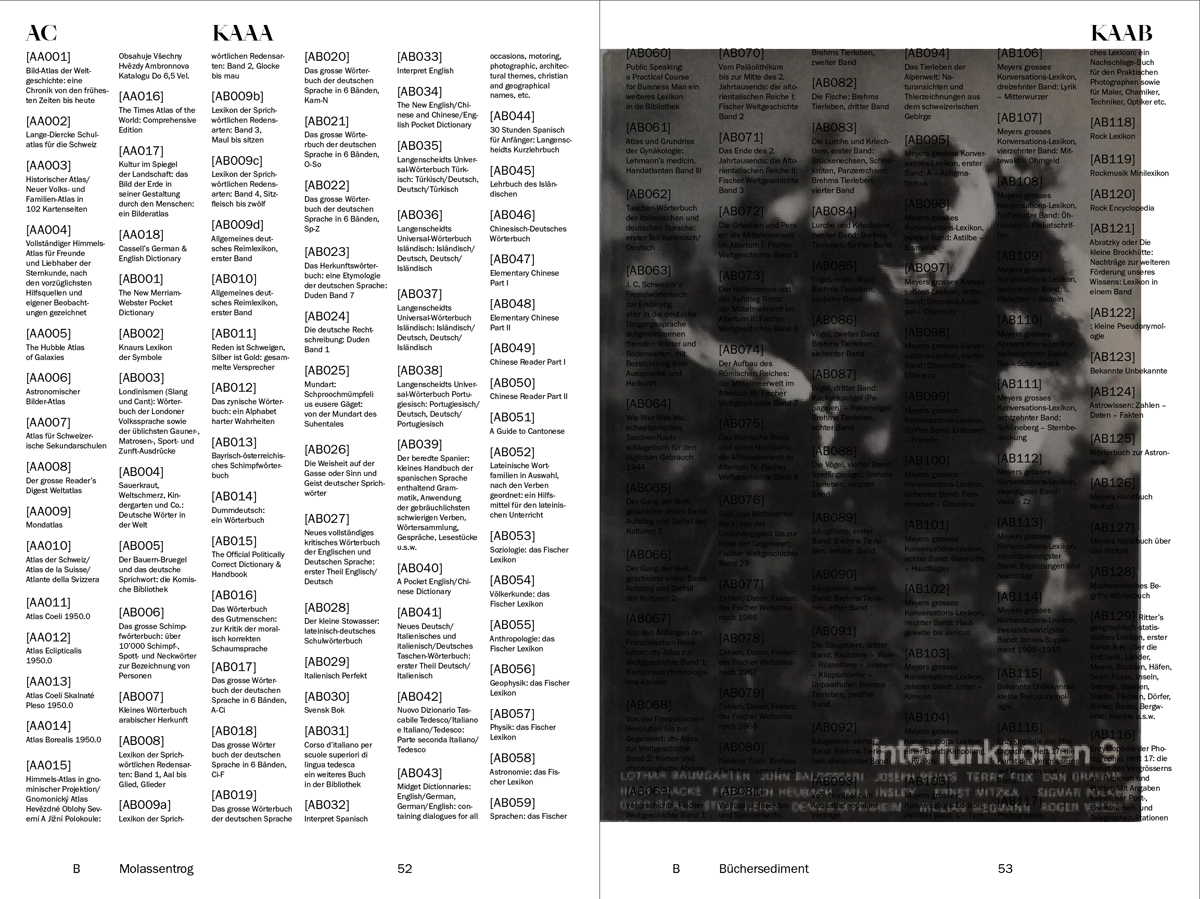

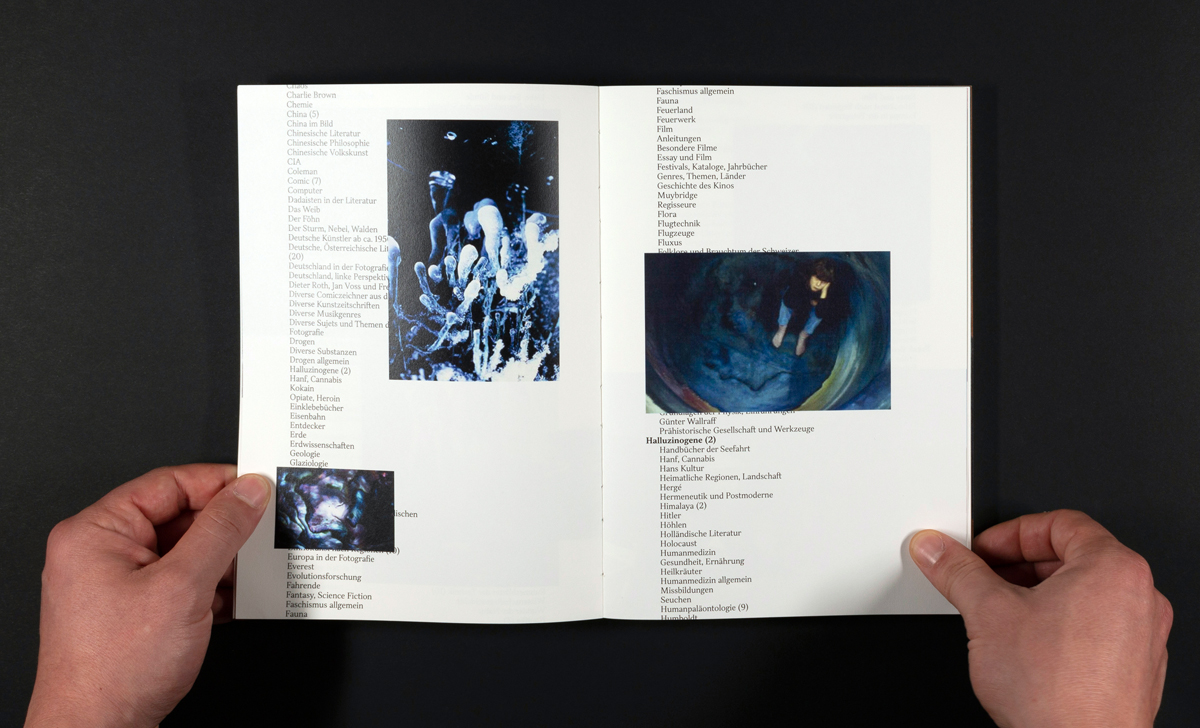

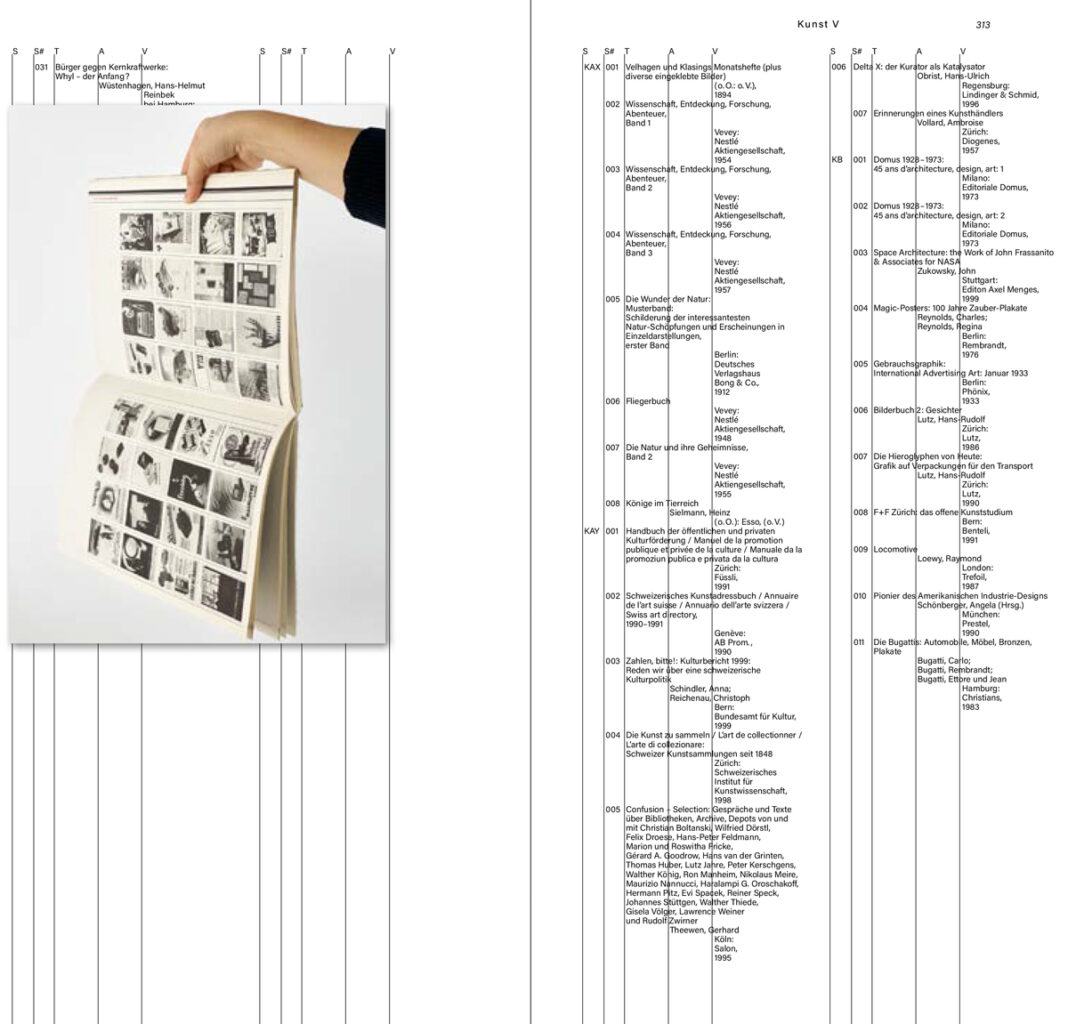

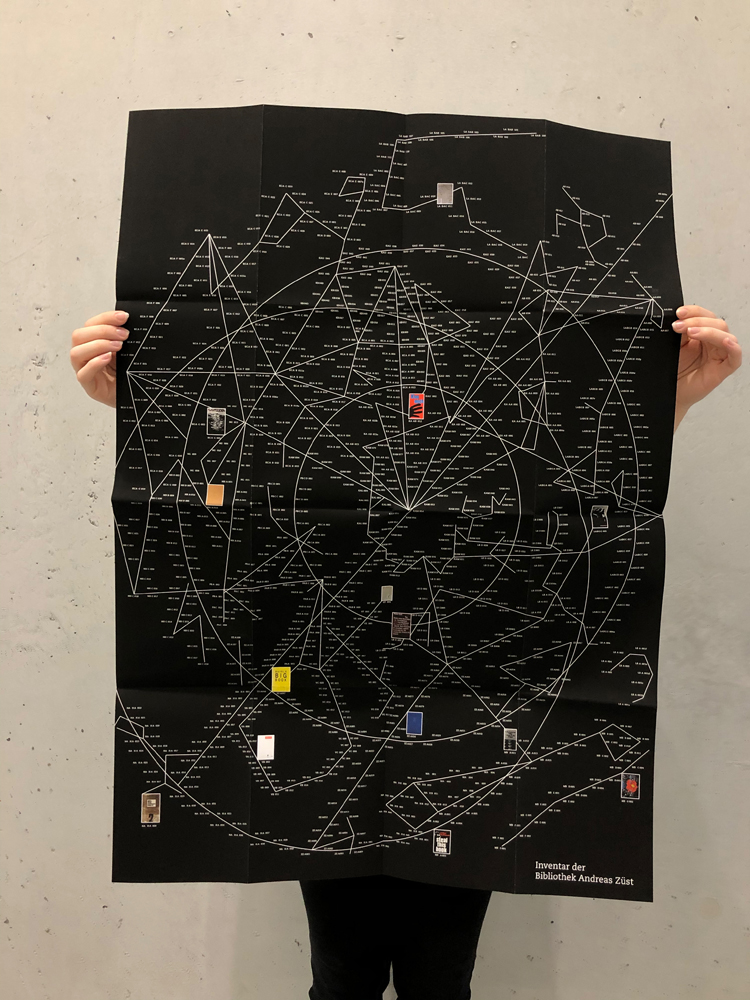

Ende September 2020 tauchten Studierende der Studienrichtung Graphic Design der HSLU D & K für zwei Tage ein ins Bücher-/Himmelmeer der Bibliothek Andreas Züst. Ausgerüstet mit Kamera, Notizblock und viel Neugierde pickte sich jede*r Student*in eine Publikation, die er*sie in den nachfolgenden sechs Wochen im Buchmodul präsentierte und unter eigenem Fokus die Bibliothek Andreas Züst porträtierte.

Alle Studierenden gestalteten aus demselben Material komplett unterschiedliche Publikationen zur Bibliothek, die in fünf Kapiteln die Geschichte des Alpenhofs, Leben und Werk von Andreas Züst, den Katalog, die Residency und ausgewählte Publikationen aus der Bibliothek vorstellten.

In der Ausstellung «Eis» von Andreas Züst, die im gleichen Zeitraum im Kunstmuseum Luzern präsentiert wurde, gewährte Mara Züst Einblick ins Leben und Werk von Andreas Züst.

Mit Beiträgen von: Liv Bachmann, Kathrin Blümli, Sara Dietrich, Fabia Lyrenmann, Claudine Misteli, Jlaria Moscufo, Sophie Müller, Simon Perler, Lisette Reidiger, David Schmidle, Meret Schneider, Salome-Jael Steinegger, Anastasiia Vitushkina, Corinne Wasser, Federica Zanetti.

Betreuung: Megi Zumstein & Valentin Hindermann

September 2020

Text: Megi Zumstein

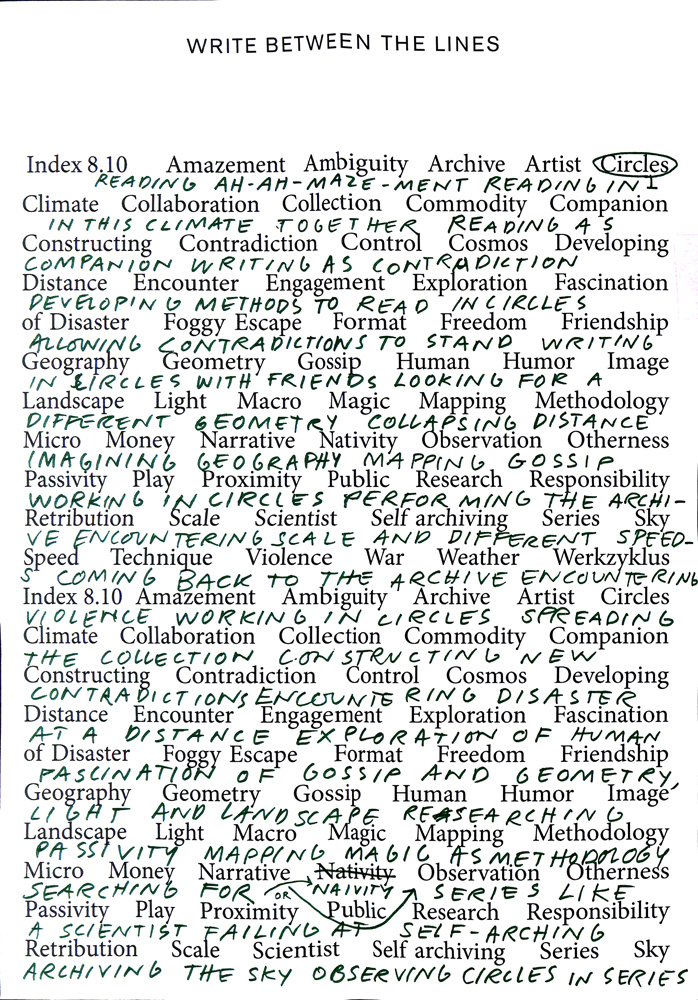

Hello, our names are Anton Weflö, Rosita Kær and Elina Birkehag. We are very happy that you’re all here. About one year ago we started a reading group together. We were sharing a studio in Amsterdam, and the reading group started as a response to our shared library. Our focus has been to find ways of expanding the format of a reading group. For 4 weeks our reading group has been located at Bibliothek Andreas Züst. Tonight we will do a reading based on a selection of texts we have been reading and writing during this time.*

“The classroom is a reading–free zone. Indeed anyone caught reading is thought somehow to have not done her or his work! Students are supposed to read at home, alone. Even study groups are supposed to discuss assignments, not spend time in each others company reading, much less reading to each other. It is almost as if reading is something about which we are embarrassed. We can do yoga together, pray or meditate together, eat together, but somehow we should read in isolation.” (10.)

“I find that in literature, no writer’s mother compares to mine. My mother, she was a great character, a comical character, too. She had all the attributes of a great character. She was capable of madness, like the affair with her land, but she also possessed a great lucidity. She embodied those contradictions that make for great characters, like when she nearly died upon learning that I enrolled in the Communist Party. But she is not the main hero of my body of work, nor the most permanent. No, I am the most permanent. Writing is to write for oneself.” (13.)

“An atmosphere of

Sha-

Shal-

Messa-

Sha-

Shal-

Cor-

Buil-

Swal-

Dia-

Twi-

Spend some tranquil moments observing this

Ope-

Swal-

Stran-

Vuil-

Cor-

I would often wander into this

Sus-

Pi-

Sere-“ **

“[…] what’s important to listeners, especially children, isn’t hearing a new tale, but how the old one is told. ‘The children make it theirs by repetition’, he says. While endless repetition of the same story may seem uninteresting to adult Americans who have come to privilege information over inflection, substance over subtlety, children everywhere still prefer the retelling of a single, familiar tale, no matter how simple, to the novelty of a new one – at least while they’re young and haven’t fully absorbed the cultural norms.” (1.)

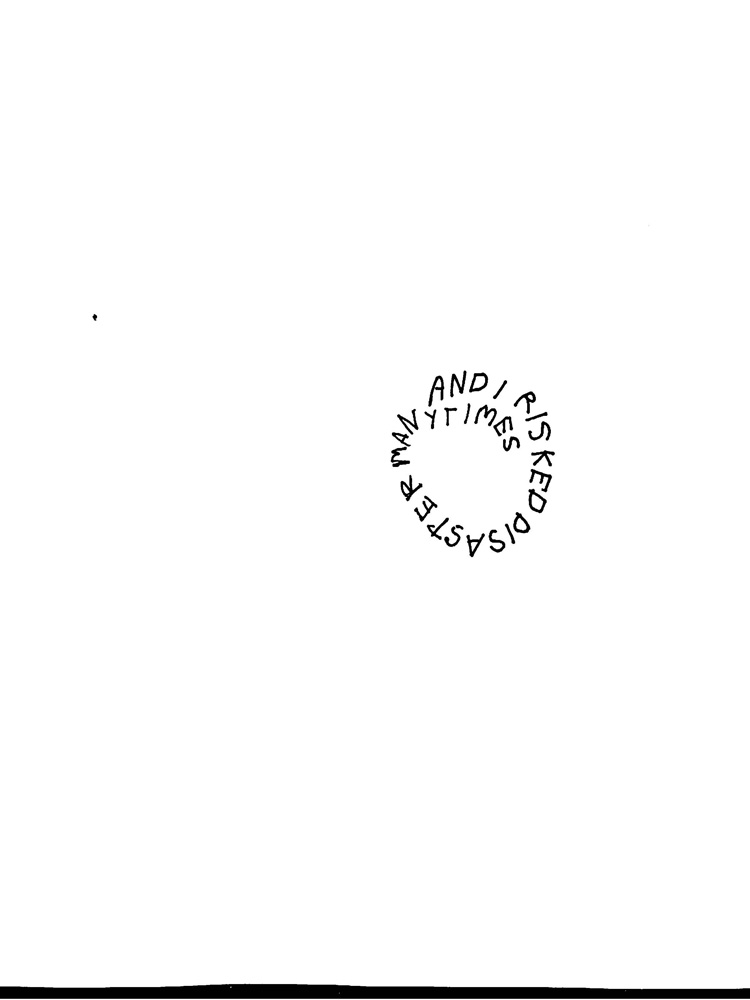

“Do you find me very foolish? Or sadly naive? Did you know that surely no one in the world has looked at the licence plates of more yellow Mercedes than I have. Infinitely hopeful, I imagined as I drove through Berlin that this lemon yellow or that yellow lemon might be your lemon yellow. And I risked disaster many times.” (16.)

*Introduction to reading at Material, Zurich, 28.11.19

**Excerpt from writing excercise

_

Bibliography

1.

Tucker, Marcia

Markus Raetz: In the Realm of the Possible

Publisher: New York : New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1988

Call Number: KADR 015

Shelf: Kunst III

2.

Stellweg, Carla

Frida Kahlo: the Camera Seduced

Publisher: San Francisco : Chronicle Books, 1992

Call Number: KACK 002

Shelf: Kunst II

3.

Iannone, Dorothy

The Art of Sarah Pucci 1959–1993

Publisher: Amsterdam : Voss Forlag, 1993

Call Number: KAG 112

Shelf: Kunst IV

4.

Iannone, Dorothy

Dorothy Iannone and her Mother Sarah Pucci

Publisher: Aachen : Neue Galerie, 1980

Call Number: KAG 151

Shelf: Kunst IV

5.

Bourgeois, Louise

Destruction of the Father – Reconstruction of the Father : Writings and Interviews 1923–1997

Publisher: London : Violette Editions, 1998

Call Number: KACB 014

Shelf: Kunst II

6.

Berger, John

Road Directions : Zeichnungen und Texte

Publisher: Zürich : Edition Unikate, 1999

Call Number: KABB 004

Shelf: Kunst II

7.

Parkett Nr. 44/1995 : collaboration Vija Celmins, Andreas Gursky, Rirkrit Tiravanija ; insert Hans Danuser

Publisher: Zürich : Parkett, 1995

Call Number: ZI 044

Shelf: Zeitschriften

8.

Laing, R. D.

Knots

Publisher: Harmondsworth : Penguin, 1971

Call Number: LBJ 010

Shelf: Philosophie II

9.

Perec, George

Brief Notes on the Art and Manner of Arranging One’s Books

http://monumenttotransformation.org/atlas-of-transformation/html/c/classification/brief-notes-on-the-art-and-manner-of-arranging-ones-books-georges-perec.html

10.

Sealy Thompson, Tonika & Harney, Stefano

Ground Provisions

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/698401?journalCode=aft

11.

Weiner, Hannah

Clairvoyant Journal

http://eclipsearchive.org/projects/CLAIRVOYANT/clairvoyant.html

12.

Bernstein, Charles & Weiner, Hannah

Interview for Linebreak

http://writing.upenn.edu/epc/authors/weiner/Weiner-Hannah_LINEbreak_1995_full-transcript.pdf

13.

Duras, Marguerite

Motherhood makes you obscene

14.

The Pleasures of Merely Circulating

Publisher: Zürich : Memory/Cage, 1995

Call Number: KAQ 073

Shelf: Kunst V

15.

Bennett, Jane

Powers of the Hoard

Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: Ethics and Objects

http://www.oapen.org/search?identifier=1004486

16.

Williams, Emmett; Iannone, Dorothy; Copley, William N.

Emmet Williams: Aleph, Alpha, and Alfala; Dorothy Iannone: Werben um Ajaxander / Courting Ajaxander; William N. Copley: Techniques of Fornication

Publisher: Berlin : Haus am Lützowplatz, 1993

Call Number: KAH 019

Shelf: Kunst IV