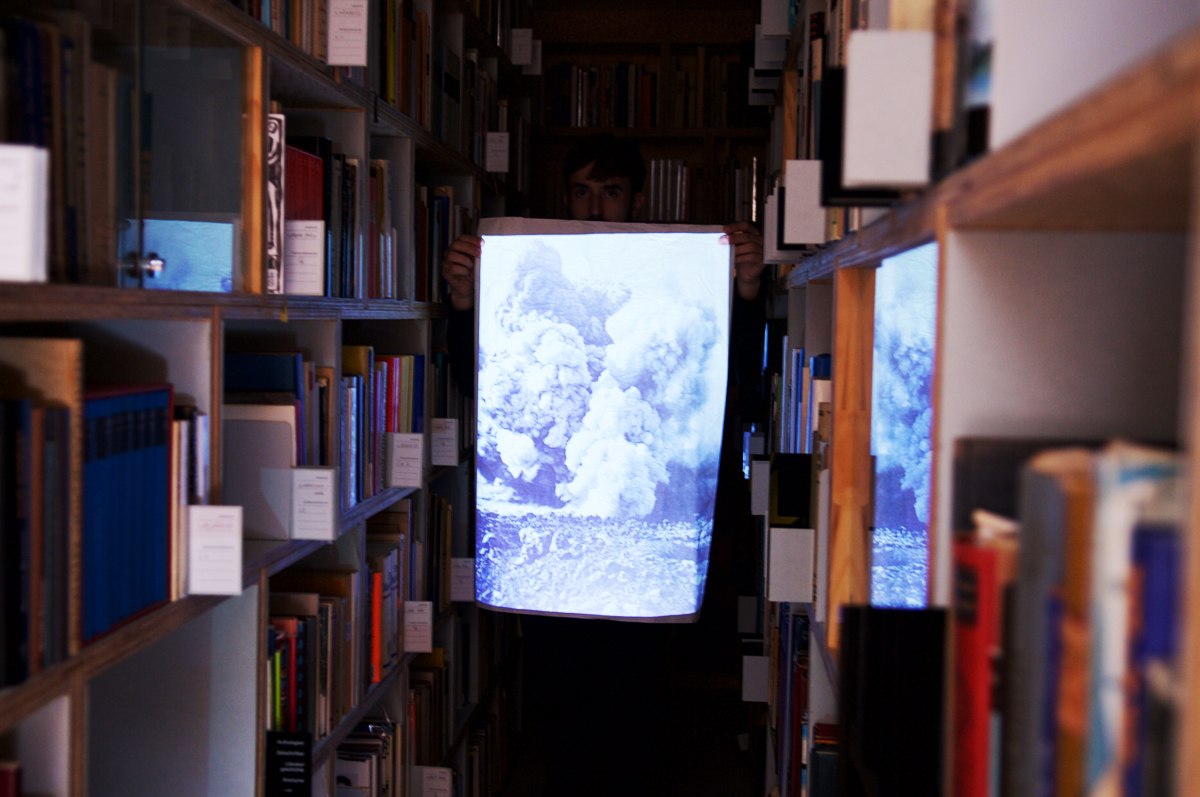

St. Anton, 1110 Meter über Meer, Appenzell Innerrhoden: Ich verbringe auf Einladung eine knappe Woche im Hotel Alpenhof und also in der Bibliothek des verstorbenen Mäzenen, Künstler und Sammler Andreas Züst. Die Bibliothek ist zweistöckig und fasst über 10’000 Bücher, das Hotel ist vierstöckig und die Zimmernummern enden bei der 27. Ich bewohne das Zimmer mit der Nummer Eins, es ist ein kleines Eckzimmer mit einem Balkon und wie unter jedem Fenster dieses Hauses steht auch unter dem Fenster des Zimmers mit der Nummer Eins ein Wort aus hölzernen Grossbuchstaben: ASKET, steht da ausgerechnet und nicht etwa Stammgast, Flüchtling, Schriftstellerin, Schlaflose oder was halt sonst noch unter den Fenstern des Alpenhofs steht.

In der Woche, die ich im Alpenhof verbringe, bin ich der einzige Gast, die anderen 26 Zimmer sind leer, nur hin und wieder kommt jemand vom Haus vorbei. Draussen spazieren tagsüber Rentnerinnen vorbei, aber nachdem das letzte Postauto, von denen es täglich fünf gibt, gefahren ist, also kurz nach Vier, ist hier niemand mehr. Manchmal heulen draussen die Hunde, Glocken werden in der Ferne geschwungen, vielleicht als Vorbereitung auf das anstehende Alt Silvester, und Abends erstreckt sich das Rheintal leuchtend bis an den Fuss des Vorarlbergs. Sobald es dunkel wird, scheint die Zeit überhaupt nicht mehr zu vergehen und dann sitze ich hier alleine in diesem Berghotel, zwischen 10’000 Büchern, im Vakuum der Askese und manchmal erschrecke ich, wenn ich raus auf den Balkon trete um zu rauchen, und das Rheintal verschwunden ist, weil sich eine Nebeldecke drübergelegt hat. Manchmal erschrecke ich auch einfach so, wegen eines Knarrens oder sonst eines Geräusches und dann schreibe ich ein paar Mal «All work and no play makes Jessica a dull girl» in ein Worddokument, als halbherzige Reminiszenz auf «The Shining», den ich eigentlich gar nie wirklich mochte und nur einmal als Teenager mit Freundinnen gesehen habe, zeitweise ohne Ton und in doppelter Geschwindigkeit, weil es irgendwem zu gruselig war.

Ich blättere mich quer durch die interdisziplinäre Bibliothek, die Schwerpunkte (Kunstbücher und Aliens) interessieren mich nicht besonders, aber Züst hat thematisch so breit gesammelt, dass das nicht schlimm ist. Ich lese drei inzestuöse Sodomie-Orgien lang in Marquis de Sade, danach eine Kurzgeschichte von H.C. Artmann, im einen oder anderen Buch der Beatgeneration, den Erlebnisbericht Emile Ammanns und Dora Kosters Autobiographie. Irgendwann entdecke ich die Rubrik «Das Weibe» und lasse mir von irgendeinem Typ aus den 50ern erklären, was frau für die perfekten Brüste tun kann: «Schöne Büste. JA, aber wie? Das Geheimnis zur Erlangung einer vollendeten Büste.» Direkt daneben steht Von Rotens «Frauen im Laufgitter». In der Fotografie-Ecke blättere ich in einem japanischen Pornoheft, in einem Fotoband über die Playboy Mansion und in einem über Marilyn Monroe. Dann schau ich noch ein bisschen bei der Drogen- und Cyberabteilung rein, Timothy Leary, «Chaos & Cyber-Kultur», mit Beiträgen von Winona Ryder und William S. Burroughs.

Einmal muss ich ins nächste Dorf runterfahren um Essen einzukaufen. In Oberegg gibt es eine Post (ohne Geldautomat), eine Bank (mit Geldautomat), einen Volg, eine Bäckerei, einen Hundefrisörsalon und einen Käseautomaten. Am Käseautomaten kaufe ich mir Eier und Käse und bin komplett gehypet und unfähig die Exotisierung des Appenzeller Vorderlands, die sich gerade in mir zusammenbraut, zu bremsen. Dabei sind das hier ja gar nicht die «Anderen», schliesslich bin in einer ganz ähnlichen Gegend aufgewachsen, nicht weit von hier, am anderen Ende des Appenzells, etwas weiter unten im Tal und den Säntis sah man aus einem anderen Winkel als vom St. Anton. Der Säntis, der ständig so unangenehme identitäre Regungen in mir auslöst, die ich am liebsten wegkratzen möchte wie unliebsame Mückenstiche oder so. Der Säntis, mein Berg, der Gipfel meiner Heimat, der täglich den Schatten Schweizerischer Identität auf meine Kindheit geworfen hatte. Und natürlich lässt sich neben der Exotisierung auch eine Romantisierung kaum aufhalten: Die Bibliothek, das verlassene Berghotel, die Aussicht vor den grossen Fenstern, der Käseautomat, die Wanderwege. Den ganzen Tag lesen und aus dem Fenster schauen oder gedankenverloren ein paar Gedichte schreiben. Es ist genau jener mondäne bohemian Lifestyle den ich nie wollte und den ich gleichzeitig als einen solchen Luxus empfinde, dass ich der Überzeugung bin, ihn nicht verdient zu haben, weil ich es mir nicht leisten könnte, weil ich eigentlich noch überhaupt nie in einem Hotel war, weil das ein Privileg ist und weil es sich aus meinem Habitus heraus irgendwie unbehaglich anfühlt. Und weil auf einem Berg chillen und den ganzen Tag lesen und aus dem Fenster schauen sowieso ein Privileg ist.

Die Gedanken an Kapital und soziale Klasse und Privilegien nagen dann auch an der Romantisierung, der Alpstein bröckelt, der Nebel zieht übers Rheintal und die Bücher beginnen zu miefen. Aber ich schiebe die Zweifel beiseite, sperre Bourdieu, der leibhaftig an mir zu nagen scheint, raus in die kalte Nacht, und sage zu mir selbst laut in die Stille hinein: Ich habe das verdient. Eine Minute später bin ich bereits misstrauisch ob dieser zu mir selbstgesprochenen Aussage, denn diese impliziert ja, dass ich mir zwar kein wirtschaftliches Kapital erarbeitet habe, dafür ein gewisses kulturelles, soziales oder auch symbolisches Kapital, womit ich mir diesen Aufenthalt erarbeitet und somit verdient habe. Aber ich will nichts verdient haben, weder monetär noch kulturell noch symbolisch, weil damit erarbeite ich mir Privilegien und Privilegien sind böse, habe ich im Internet gelernt. Ich will, dass alle gleichviel haben. Aber es ist halt immer noch Kapitalismus.

Einmal besucht mich eine alte Freundin in meiner Isoliertheit. Wir kennen uns unser ganzes Leben lang schon, unsere Mütter sassen damals hochschwanger zusammen und kurze Zeit später kamen wir auf die Welt, im Appenzeller Hinterland, sie genau eine Woche nach mir. Sie schaut sich um, streicht über ihren Bauch, in welchem sich gerade ein Kind zusammensetzt und meint, dass das zu mir passen würde, die schönen grossen Fenster, die Aussicht, die Bibliothek. Der Luxus. Und was sie damit eigentlich meint, ist doch nichts anderes, als dass es nicht falsch sei, dass ich hier bin und dass ich mir auch gar nichts zu verdienen bräuchte. Und Bourdieu, der ist draussen in der kalten Nacht erfroren, vielleicht von den Hunden zerfetzt worden. Oder die Silvesterkläuse haben ihn gefunden, bei sich aufgenommen und liebevoll aufgepäppelt am Kachelofen.

Der Alpenhof und die Bibliothek Andreas Züst ist in jedem Fall einen Besuch wert. Samstags von 13 bis 17 Uhr ist die Bibliothek öffentlich zugänglich. Zweimal im Jahr werden Residenzen ausgeschrieben, worauf jeweils hunderte von Bewerbungen folgen, wofür man also eine Menge kulturelles Kapital braucht. Einfach so Ferien im Hotel kann man auch machen, wofür man wiederum ein Menge an wirtschaftlichem Kapital braucht. Und: Privilegien sind übrigens mehr Symptom einer kapitalistischen Logik, als intrinsisch böse. Privilegierte Menschen sind vielleicht manchmal böse, oft aber auch einfach nur ziemlich unreflektiert.

Januar 2020

Text: Jessica Jurassica

Als Beitrag erschienen beim KSB Kulturmagazin.

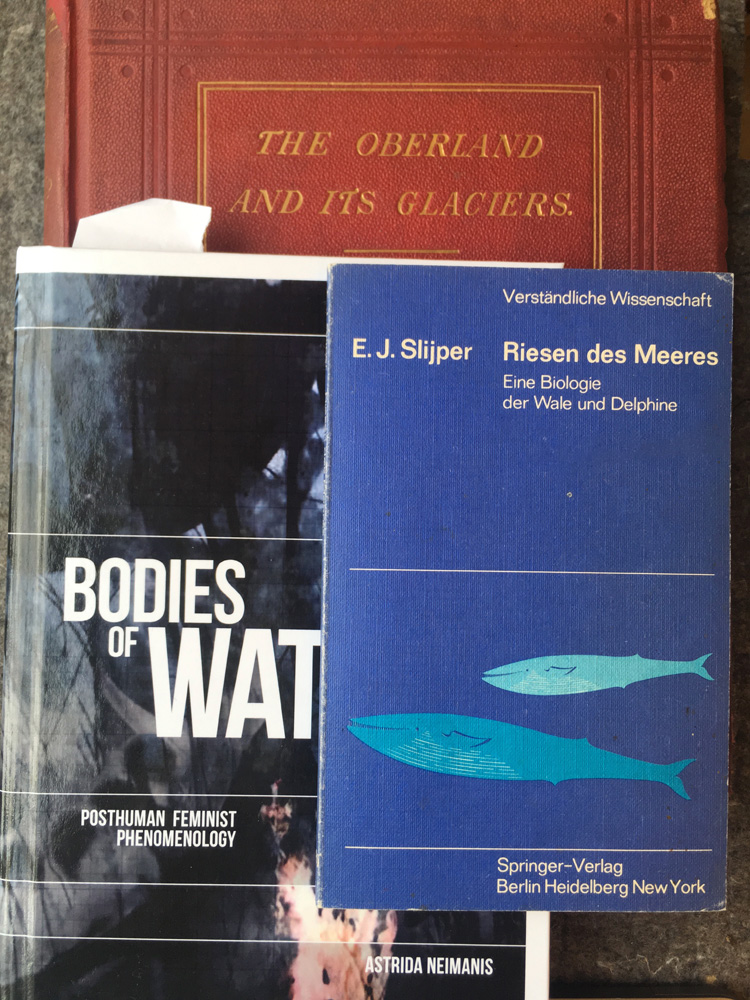

During the one-month residency Sarina Scheidegger and Jimena Croceri investigated the fluidity of glaciers in relation to (hydro)feminism, water rights and hydro commons within the library of Andreas Züst. In their performance “Nosotrxs, Cuerpos de Agua (Part II)”, Jimena Croceri and Sarina Scheidegger explored the fluid conditions which are inherent in our bodies, the sea, the waves, coconuts and glaciers. Through a variety of sonics, movements, texts and objects, they engender a sense of physical interconnectedness with its surrounding. Enacted through repetition the performance demonstrates the potentiality of intersections across difference and connectedness, between closeness and distance, between an inside and an outside.

They showed an extract of the performance at Material Zürich and then later on the performance was shown at Cabaret Voltaire Zürich and Raven Row Gallery London.

April 2019

Text: Jimena Croceri & Sarina Scheidegger

A

wechselseitige Abhängigkeit

additiv

Agitation

Agora revisited

Akephalie

Alltag

Anarchie

ausstrahlen

B

Begegnung des Zufalls

Bewegungsprinzip

Blickrichtung

C

D

Dyskommunikation

dazwischen sein

E

Ebenenwechsel

Eintritt

Ephemera

F

Feuer

G

Geduld

stundenlange Gespräche über Tagesereignisse

Glitzer, Glitzer

H

kollektive Handlung

Handzeichen

hermetisch

Hinterzimmer

I

Infrastruktur

Inseln

playful iteration

J

K

Kapseln

Klan

Kleinstgruppen

Knotenpunkte

Komitee

Konglomerat

kleiner Konsum

konspirativ

L

liegen

M

Masse

Mikrokosmos

Moduswechsel

mythische Geografie

N

nicht locker lassen

O

öffentlicher Raum

Ordnung

Opposition

P

Palast der Zerstreuung

Palace of Chaos

peripher

Perspektive

Pflege

Plateau

Q

R

S

Salon

Schattenwirklichkeit

segmentäre Gesellschaften

semipermeabel

sichtbar werden

Solidarität

Spektakel

spontan

Symbiose

Syndikat

T

Tafel

Transformation

Das Ganze ist mehr als die Summe seiner Teile

U

Übernahme

unebenes Terrain

unter freiem Himmel

V

verbindendes Element

Verdichtung

Vermittler*in

W

wandeln

weitertragend

X

Y

Z

Zentralität

Zeremonie

Zufall

multiple Zugänge

Zusammensitzen

April 2019

Text: HEFT (Ina Römling & Torben Körschkes)

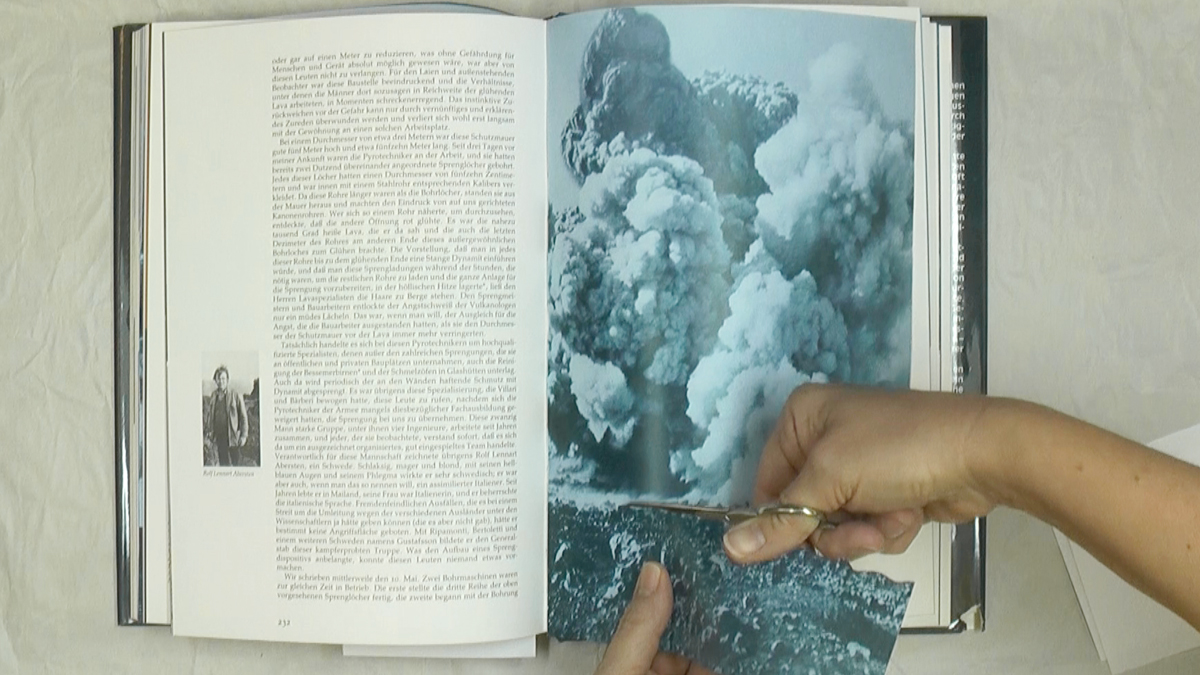

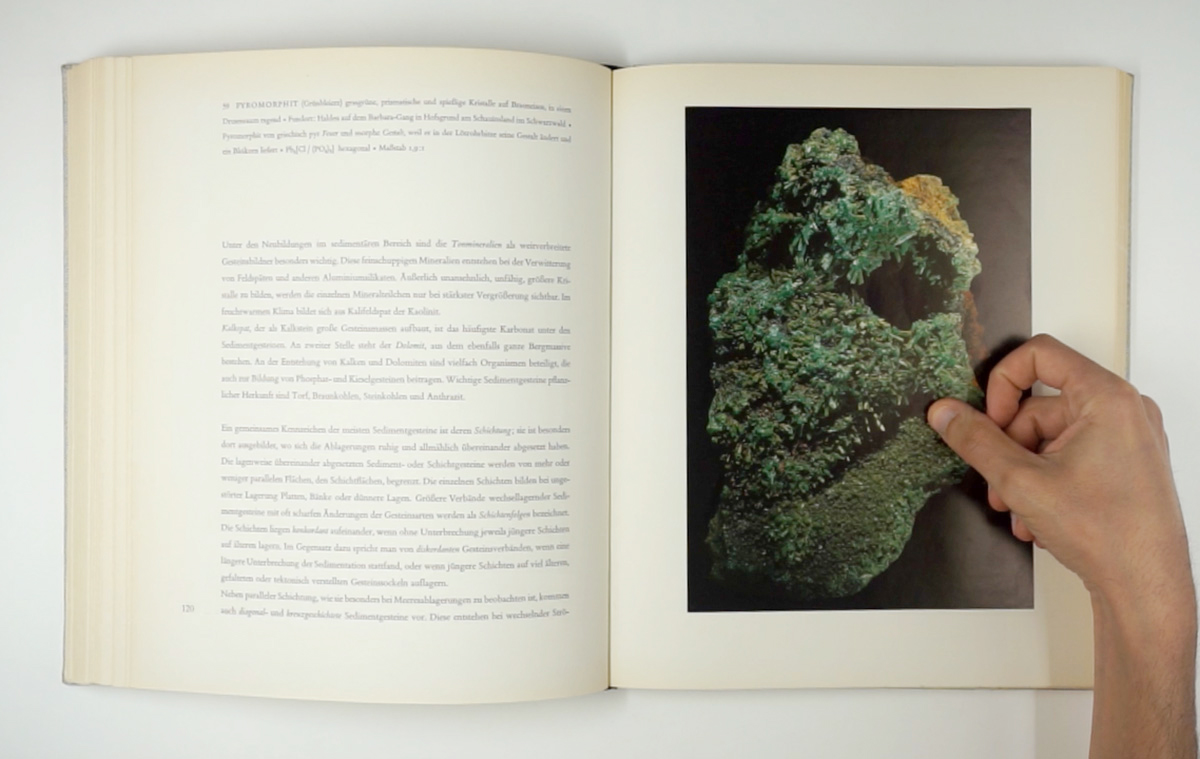

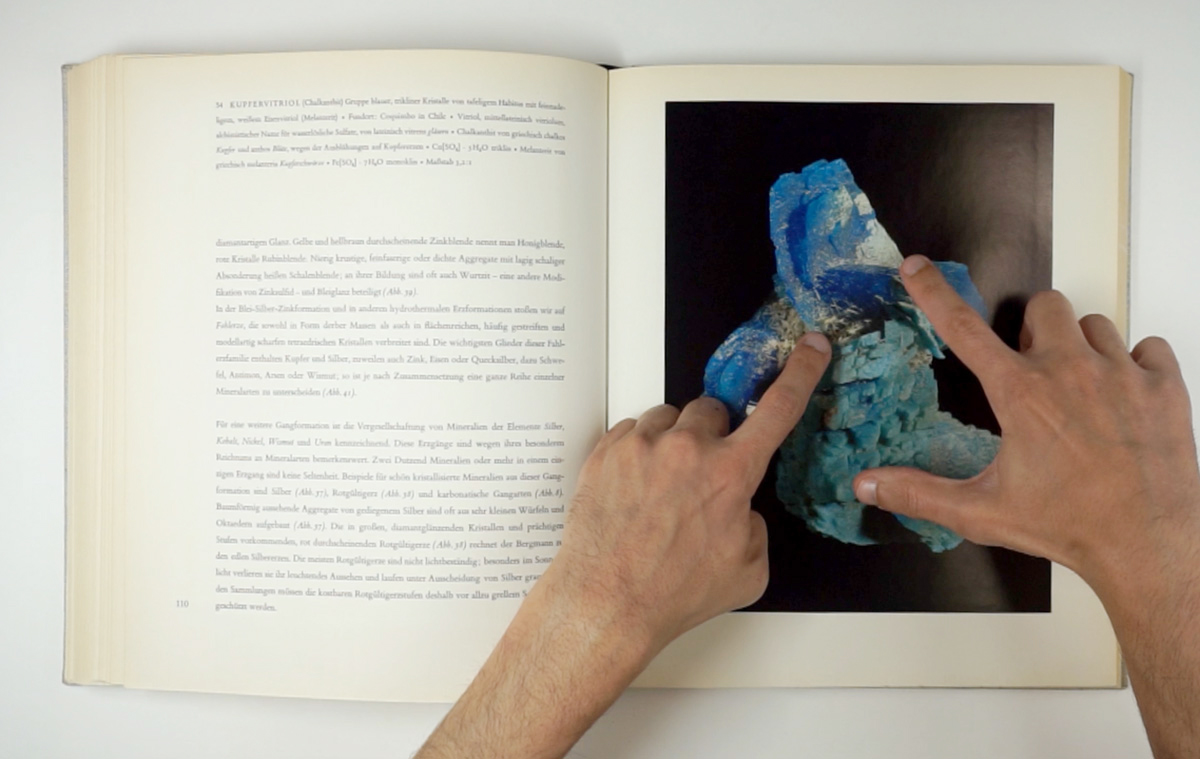

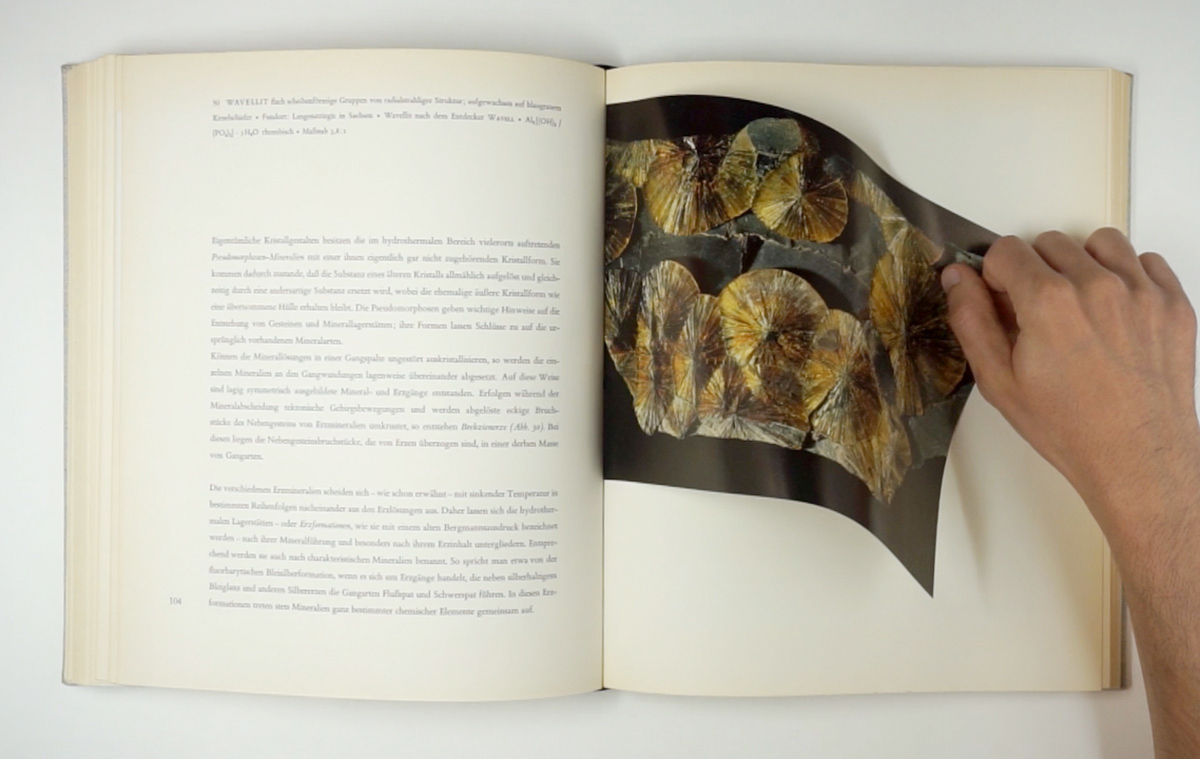

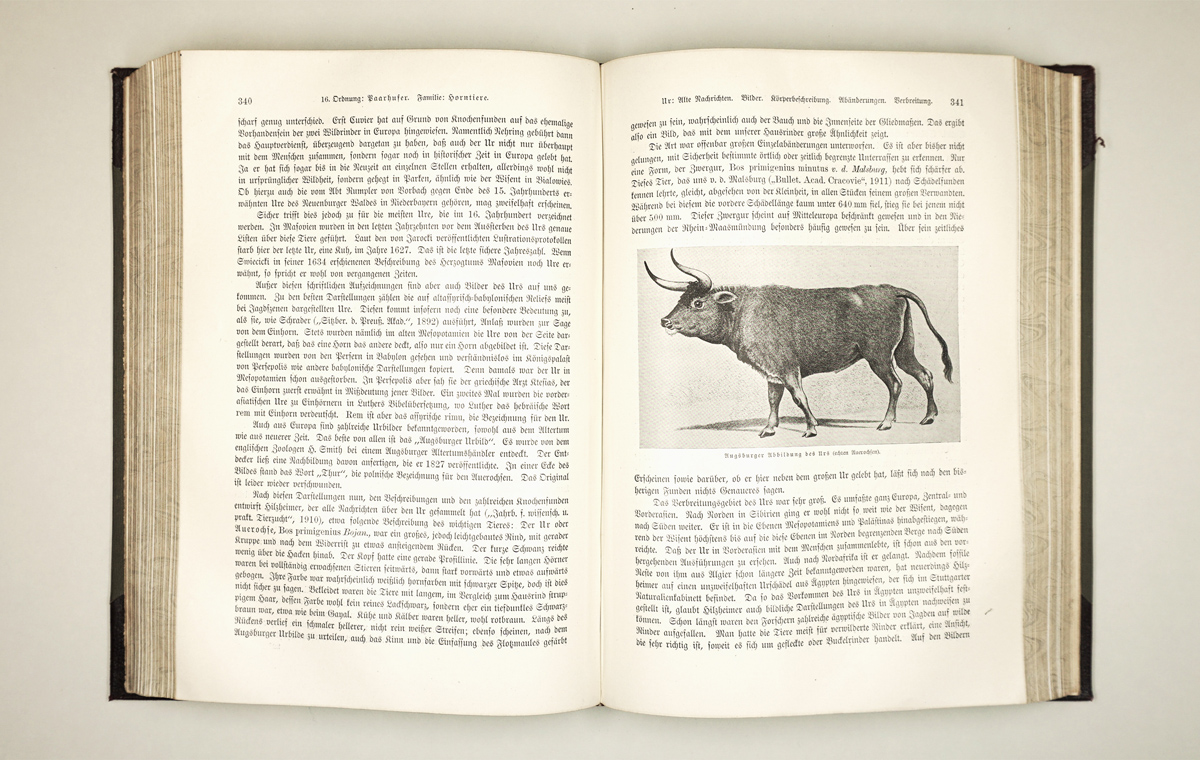

In the Andreas Züst’s library, the session Geologie in the shelves is at eye level. It comes before the session Vulcanologie and Terremotologie. Palenteology – Geology – Terremotology – Mineralogie – Caves – Glaciologie, are side by side in the ground floor. They form a horizon of related subjects making one entire side of a corridor, as a line drawing a chain of mountains.

Above these shelves there are books on Meteorology, Winds, Storms, Natural Hazards, Climate, Climate Change, – it is the sky above the geologic layer. On the other side of this configuration of weather and geology, we find Astronomy, – as a complementary opposite. Above the line at eye level on the side of Astronomy, there is an important block on the subject of light, physique and chaos. This block of content forms the universe, one where the sky touches the Earth. Or, seeing this single wall with shelves on two sides we study Earth with weather on top hiding the universe on the other side.

One Volume: In the Great Alaska Earthquake of 1964, published in the Human Ecology collection of the National Academy of Sciences in Washington D.C. in 1970, “Lessons for coping with disaster” comes after the “Impact of the Earthquakes”.

In the studies of the post-disaster period (Appendix), it is first analysed the Migration data. Then comes the Measurement of School Enrolment. – School frequency measures trust on the land. Education gives stability, or a ground.

The Economic Effects of the Disaster (p. 58) were analysed before the Impact of the Event on Health and Mortality (p. 77). What does this choice of sequence mean?

In “Lessons for coping with disaster” the author writes about the issue of warning. He says: “The movement of the ground in earthquakes of moderate or severe intensity is so obvious that the events provides its own warning signs”. After that, he lists actions that will minimise the probability of injury and death’: 1. Move as quickly as possible to locations where falling objects cannot hit you.

Another volume: In the book Confronting Climate Change – Risks, Implications and Responses, from 1992, editor Irving Mintzer first asks, “What do we know so far about the foreseeable dangers of climate change?” At the end of his introduction, he says “climate change offers an important and unique opportunity to use the threat of global environmental change as a vehicle for expanding international cooperation”. The word “opportunity” seems inopportune in 2018, it can be associated to the arrival of a new market, – which in reality it is. Cooperation may also be less humanitarian than we would think, as it may be tied to the benefit of some.

In the organisation of contents, “The Science of Climate Change” comes before the “Impacts of Global Climate Change”. As it is, explaining and discussing climate change adds negatively to its impacts, it delays the elaboration needed from understanding the impacts themselves. It is as if a patient before being treated needed to listen to the doctor presenting his professional life.

The only photograph in this book is of the surface of Mars. In the page before the picture, an analysis of the “vanished greenhouse of Mars”. We may think the author considers Mars to be our future: frozen. But afterwards, it says Earth averted the deep freeze of Mars because the Earth’s crust has remained geologically active. We thank the volcanoes and all tectonic movements, other disasters etc.

In this book’s index under the letter “w”: “Wait and see strategy”. See also “Business as usual” scenario; “No regrets” strategy. After all other “w” entries, comes the final Worst case scenarios.

November 2018

Text: Mabe Bethônico

A pile of books. A wall of books, a barricade, a rampart.

To dig a hole in a pile of books, to gently caress them, to give and feel pleasure, the wisdom of pleasure (never the other way round).

During my stay in the library I have tried to hold all the books I could. I have touched every one of them and felt the smell of many. I have heard the sound of their different papers and, from all of that, built a weightless portrait of many things that might have been overseen other times these books were read.

It was an exercise of approaching the library from pleasure before wisdom and, in doing so, recognizing the wisdom that lies within pleasure, a knowledge often missed out that felt eager to be felt.

If you hold a stone

Hold it in your hand

If you feel the weight

You’ll never be late

To understand

(Caetano Veloso)

November 2018

Text: Theo Firmo

I found myself wandering through the narrow corridors of a vast library, right at the very top of the mountains. Staying steady on one path was a difficult task in such an extensive archive. However, I could hear a mysterious bell singing constantly, every time I turned a book’s page.

These humming bells seeped through the book bindings as if they were the clouds slowly emerging behind the mountains. I found you there first. You were posing as the object of the painting, the detailed rendering of the scientific book, and on the embroidery patterns. I saw your happy portrait on the chocolate wrapping paper and on the wooden souvenirs. You were peacefully grazing on the steep hills, above the clouds; a vision of your silent plot.

It came as no surprise when the book’s spines turned into the warm animal back. The crisp white pages felt like sweet milk. The endless lines, every path you roam. The words, the rambling hoofs on the grassy slopes. Your breath, the steam of the grass and the echo of the clouds: the valley was the open book. You also told me the story of how you spend your time amusing yourself by imitating the shape of clouds and how they replied back with the same games. I couldn’t tell if I was in the library or on the field, the inner and outer world seemed the same.

It was clear then that the library and the valley shared a common substance: the space created by the books, between all the timelines and phenomena and the projection of every desire, was a dreamy construction, as was this vertigo caused by the clouds and the cows playing above them.

November 2018

Text: Marianne Hoffmeister Castro

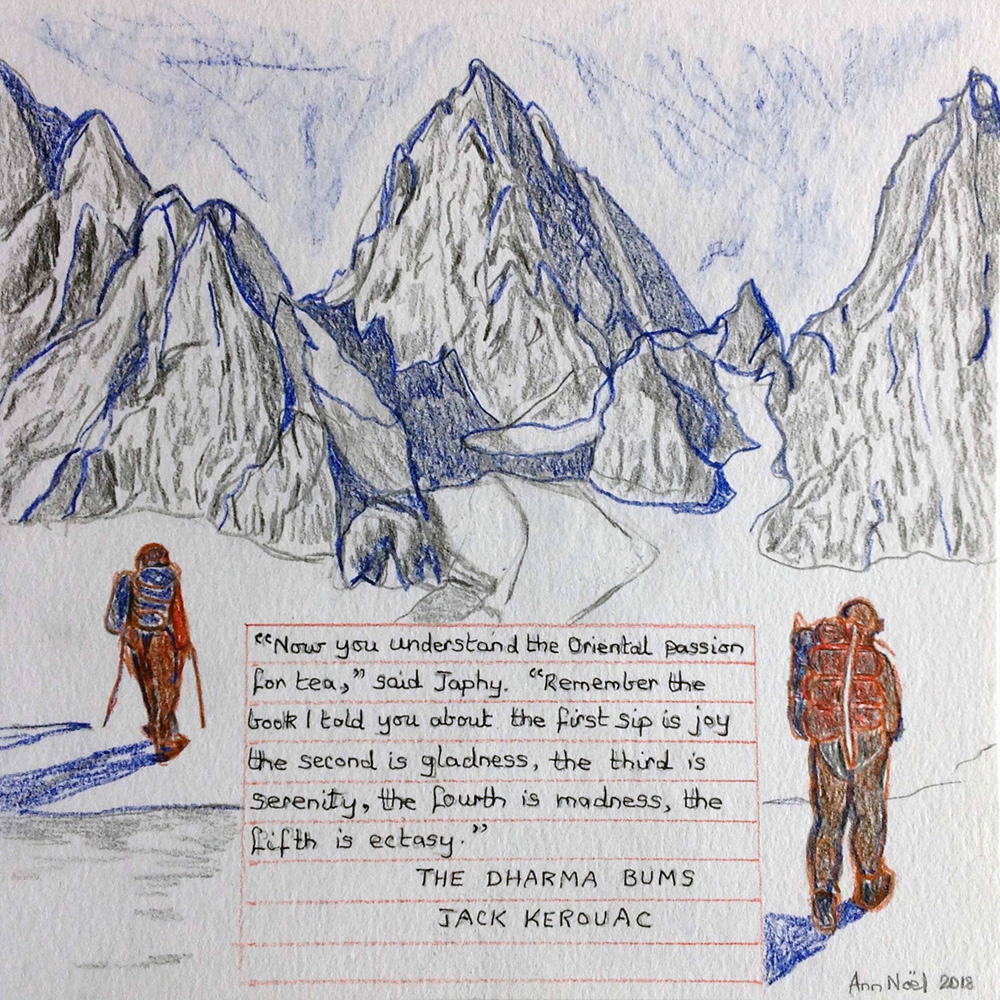

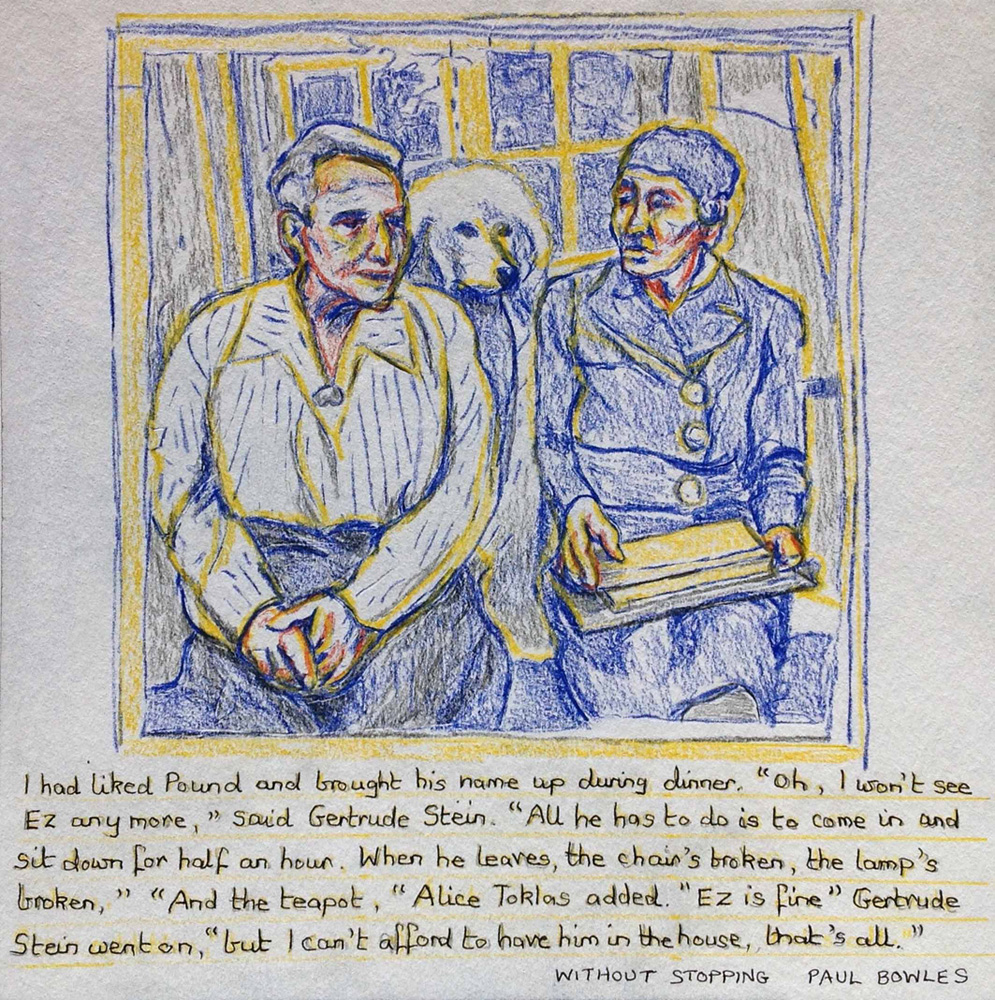

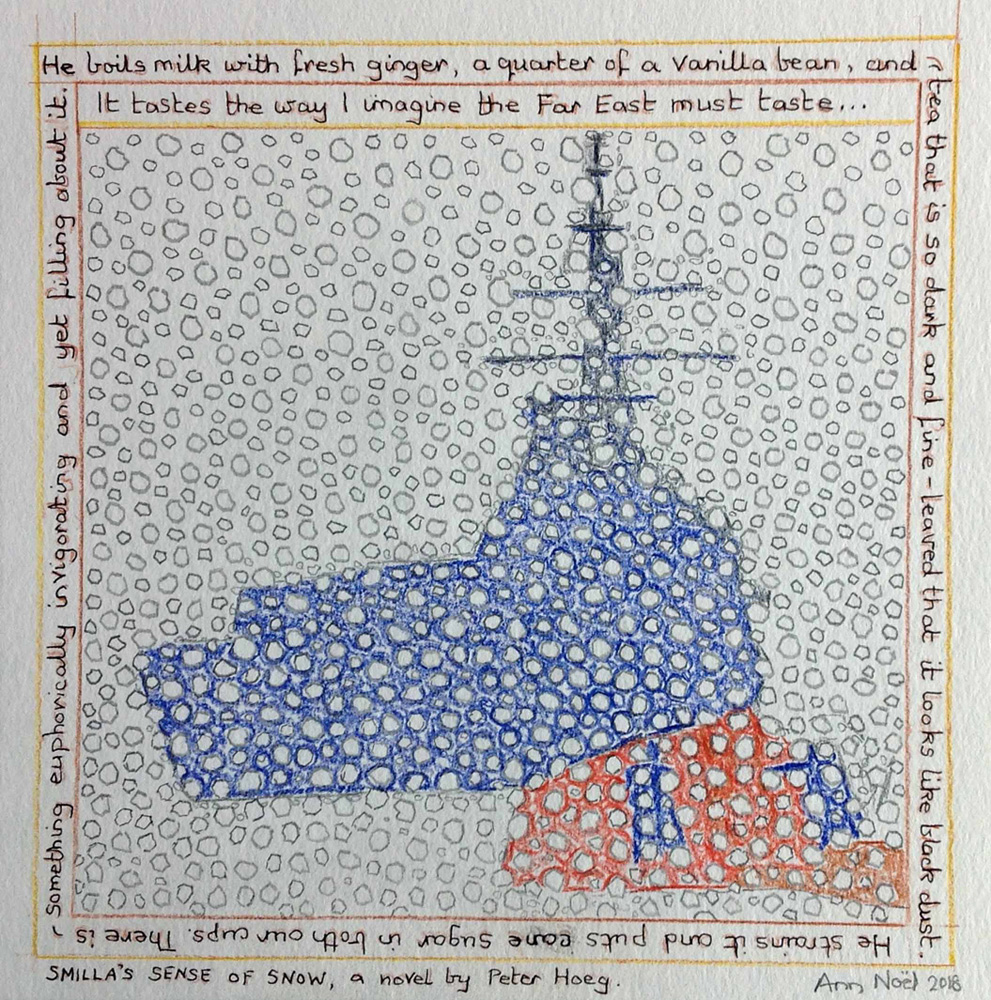

Where does one start in such a comprehensive library? I am familiar with many of the books by artists, so I began downstairs with music, literature and world phenomena. A book on the Channel Islands caught my eye, (I grew up there,) and right next to it, one about the AINU OF JAPAN, a hairy aboriginal tribe, who made moustache lifters to drink their ceremonial wine. Chinese maidens in the Ming Dynasty laughed so much they spilled tea all over their robes, while an explorer in Mongolia had to strain water though charcoal to make it palatable. The Irish Islander didn’t know what the stuff was when crates of it washed ashore after a shipwreck. Gary Snyder wrote a poem about delivering Guernsey milk by bicycle and Jack Kerouac drank tea with him on the Matterhorn in California. When Ezra Pound came to for tea with Gertrude Stein, Alice complained that he broke the pot. Miss Smilla was smitten when the mechanic made spicy tea for her during a snowstorm… I drank no tea at the Alpenhof.

November 2018

Text: Ann Noël

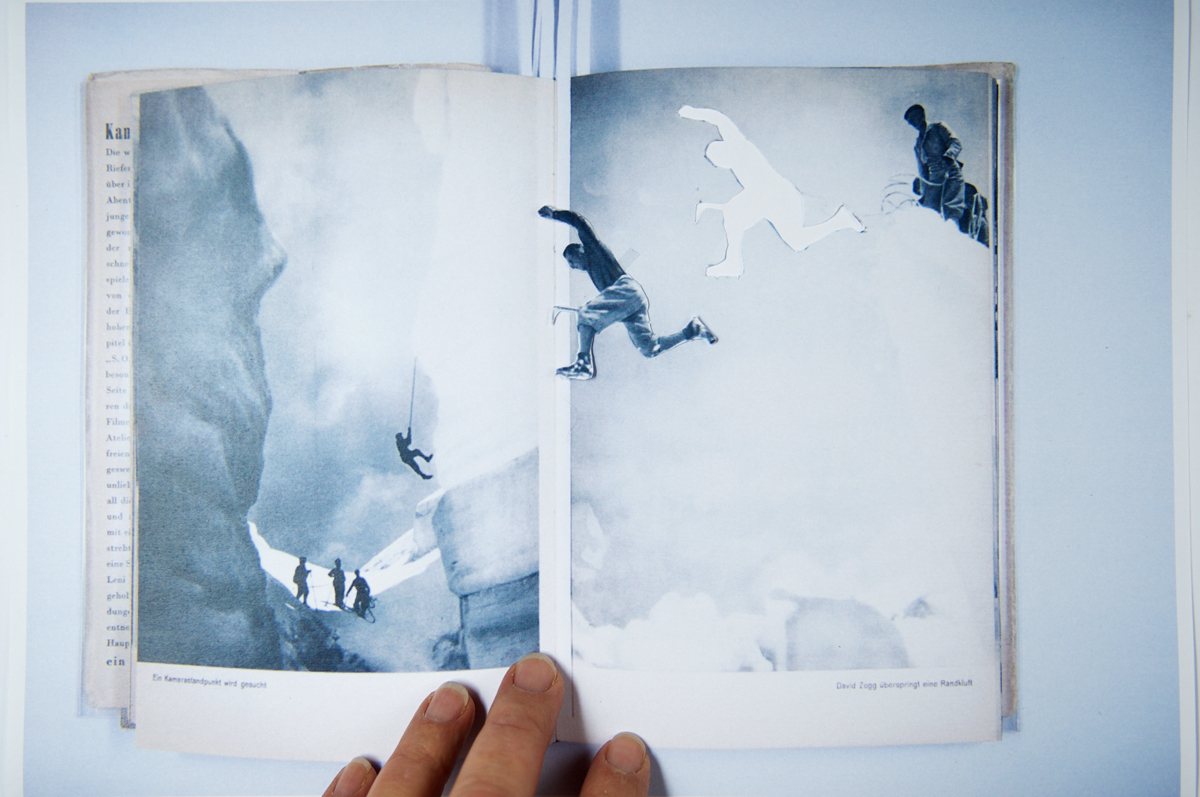

F(ai)tichism is about production and books. Books as objects of desire, subjects of an obsession which the collector Andreas Züst beautifully suffered of. F(ai)tichism is about manipulation of content, production of form and circulation of knowledge. It’s about the act of making (‘faire’ in French) triggered by the very eclectic, dense, sometimes useful, sometimes merely enjoyable knowledge contained in Züst’s library.

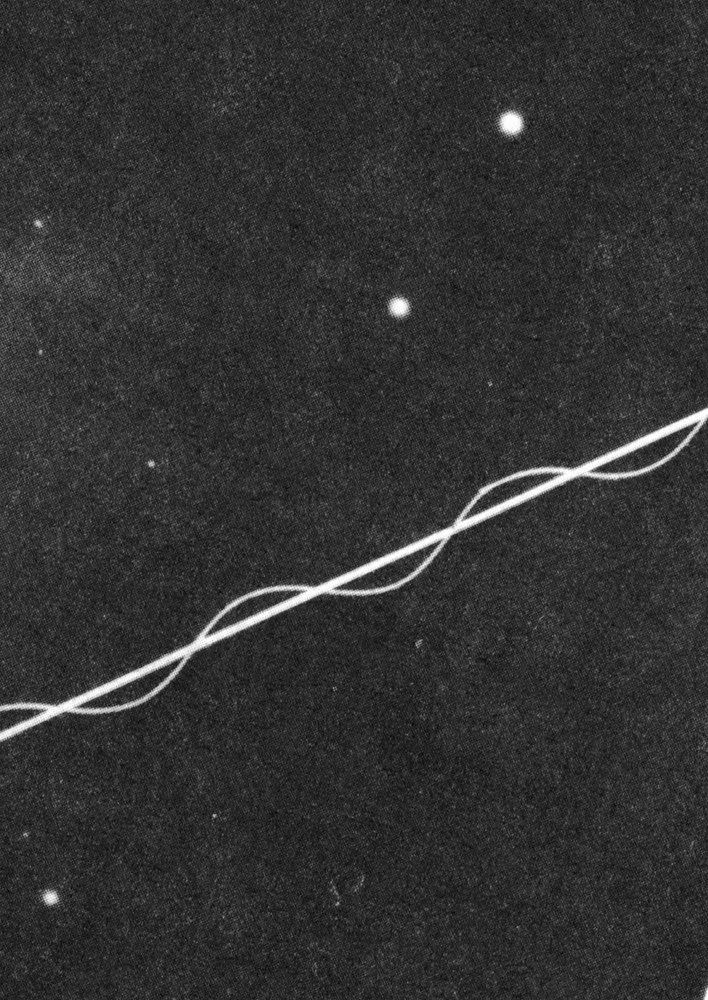

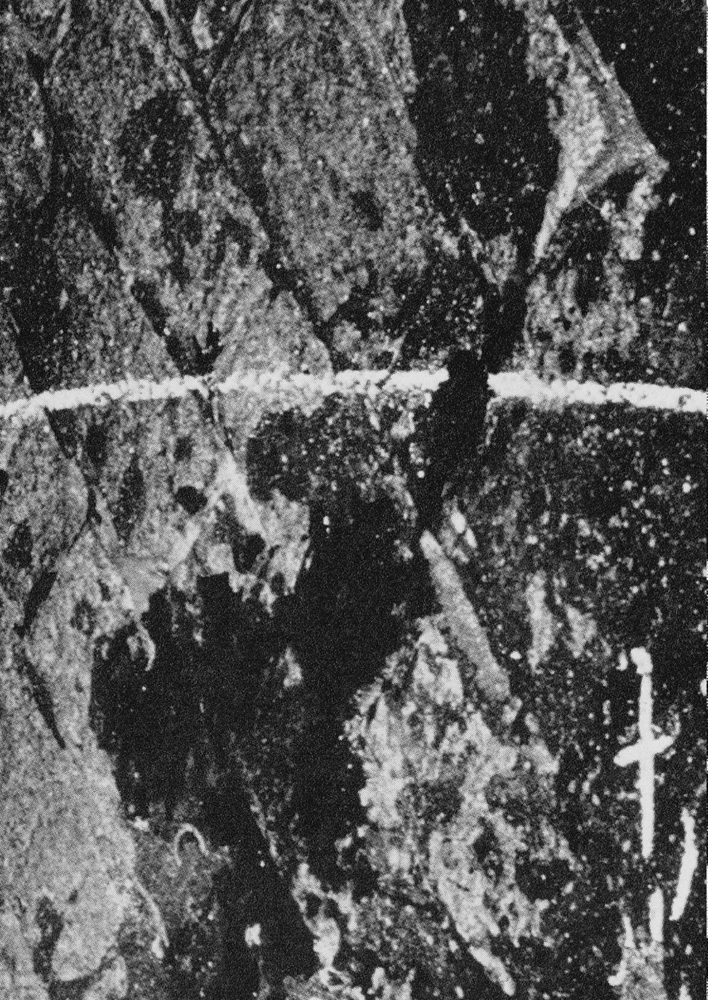

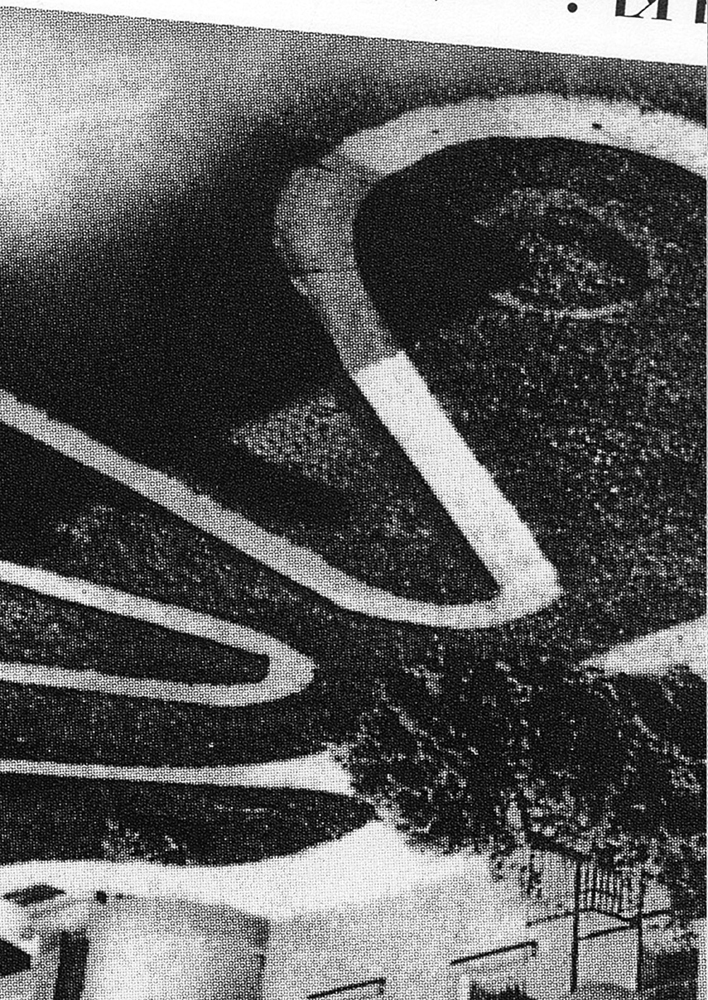

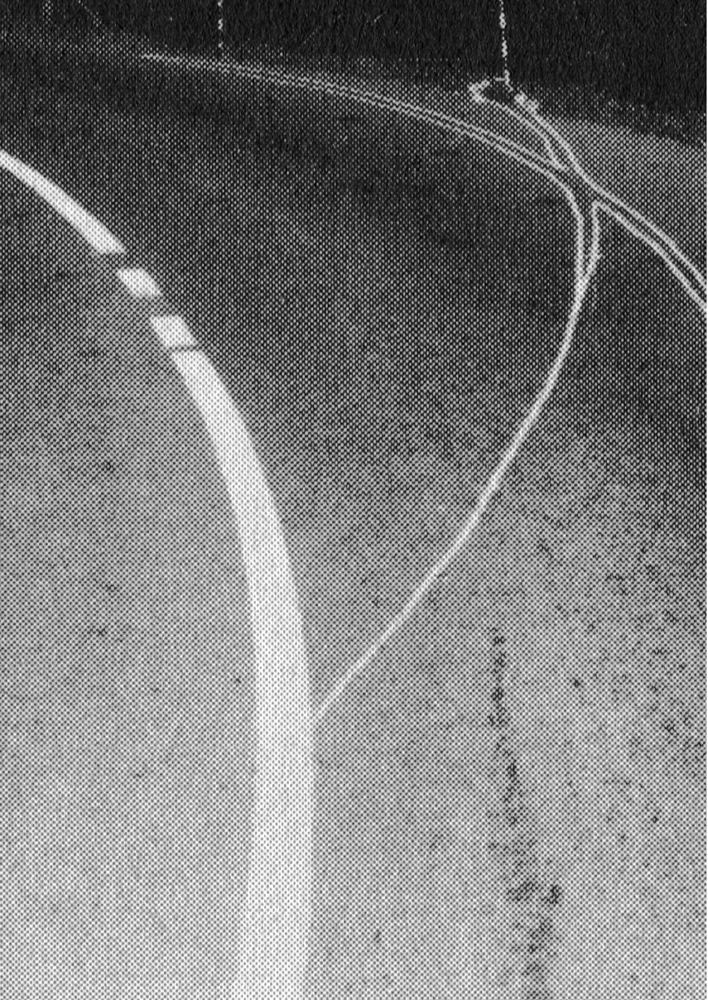

F(ai)tichism is a platform gathering 4 different outcomes, produced in 4 weeks, created after 4 different publications, subjectively picked within this very personal library. A restrictive selection built up around one common thread: the line.

Week 1: Line as a path

Selected book: ‘The Peruvian Ground Drawings’ by Maria Reiche, Kunstraum München E. V.

Outcome: A series of prints (+ bonus series of videos)

Week 2: Line, trace and measure

Selected book: ‘Grafik’, Sol Lewitt

Outcome: An installation

Week 3: The written line

Selected book: ‘Silence’, John Cage

Outcome: Two sound variations

Week 4: The straightening/straitening line

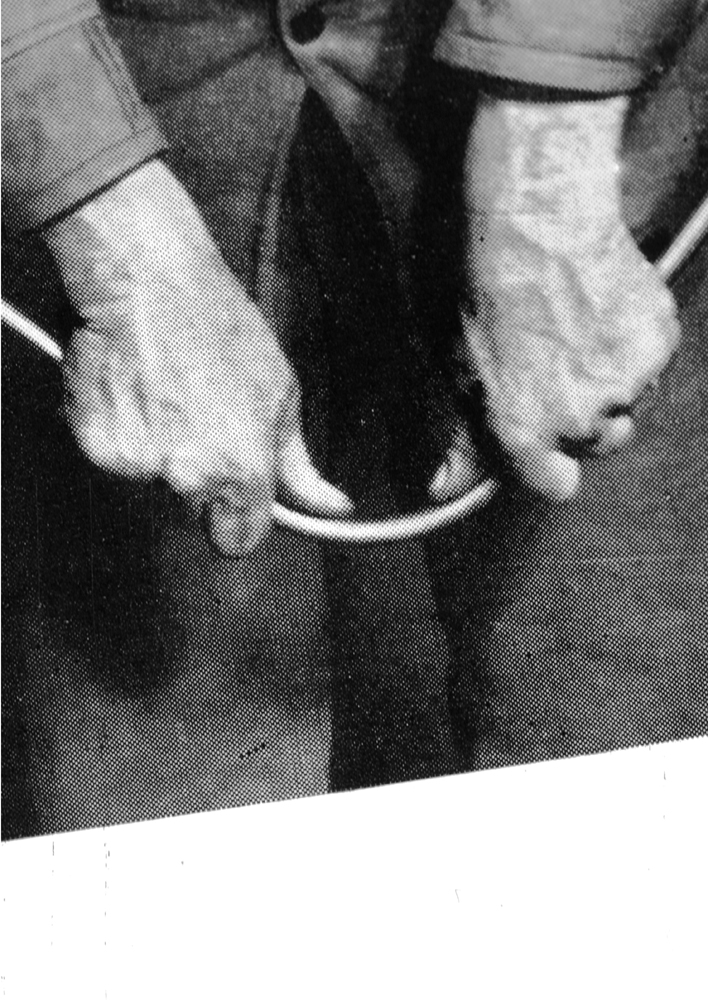

Selected book: ‘Minimo-Pendel und Widerstands-Apparate’, Dr. Caro

Outcome: A publication (+ bonus animation)

Explore F(ai)tichism here: www.faitichism.ch

April 2018

Text: Virginie Gauthier & Christof Nüssli